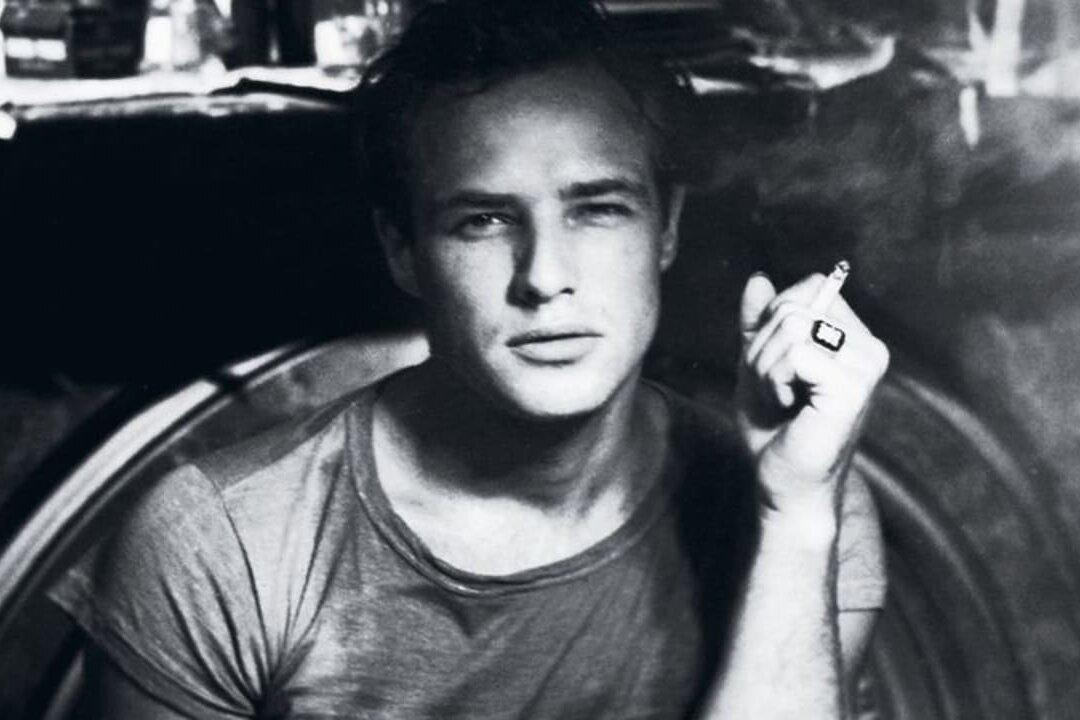

For the entirety of his 50-year film career, Marlon Brando was viewed as an artistic genius, an eccentric wingnut, a political rebel-rouser, a serial philanderer, a human rights advocate and (to some) the greatest actor of all-time. Truth be told, he was some or all of those things and much more, and thanks to audio recordings he made throughout his life, we are we able to gain significant insight into the core of the man as he viewed performing, the world, and himself.

Had this film been made while Brando was still alive (he died in 2004), it might have come off as a reputation-salvaging vanity project. Although self-absorbed to detrimental levels, Brando never sought off-screen notoriety, staunchly avoided revealing details of his personal life and never used his celebrity status for the purpose of self-promotion.