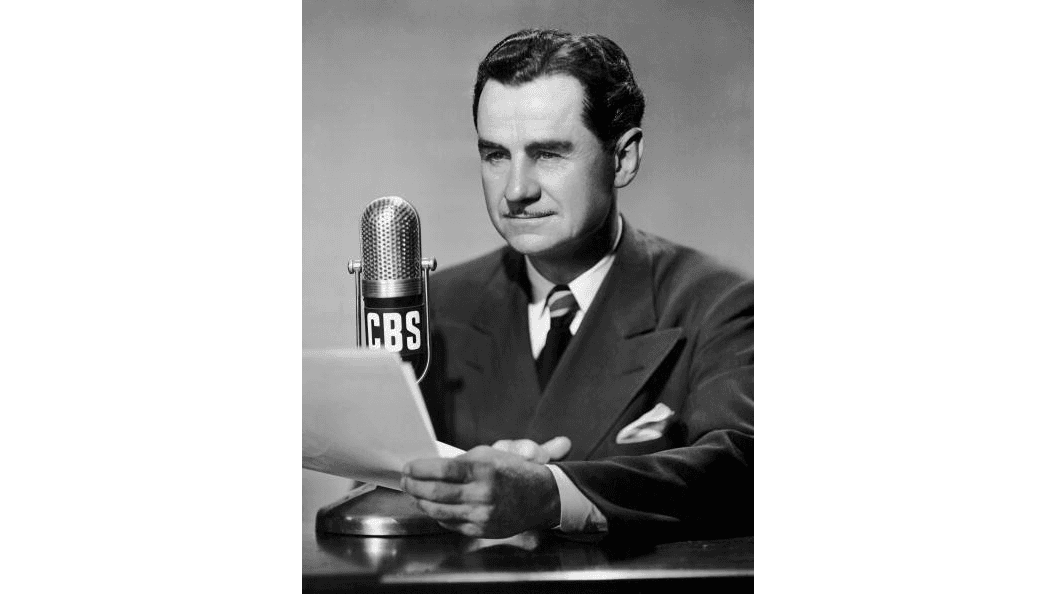

“Good evening, everybody!” This was the salutation Lowell Thomas (1892–1981) gave every weeknight for more than 45 years. Thomas was the voice tens of millions of people listened to on the radio to find out what was happening in the world. Lowell, however, didn’t live his life behind the microphone. He lived more broadly than almost any person of the 20th century, and he broadcast his exploits and those of others whenever he got the opportunity.

Born in 1892, Lowell came into the world at the perfect time for harrowing adventure and incredible danger. After earning his master’s degree from the University of Denver in 1913, Lowell became a reporter in Chicago, where he also pursued a law degree at the Chicago-Kent College of Law. His writings included rail travel, as well as investigative pieces.