During the mid- to late-1800s, revolution swept through Latin America. Most countries were politically dominated by the Liberal and/or Conservative parties. Nicaragua was a latecomer in the revolutionary movement. The country had been under Conservative rule for about 30 years before the party splintered, and the Liberals shoved their way to power in 1893 with military assistance. José Santos Zelaya became president of Nicaragua, a position he would hold for nearly 20 years.

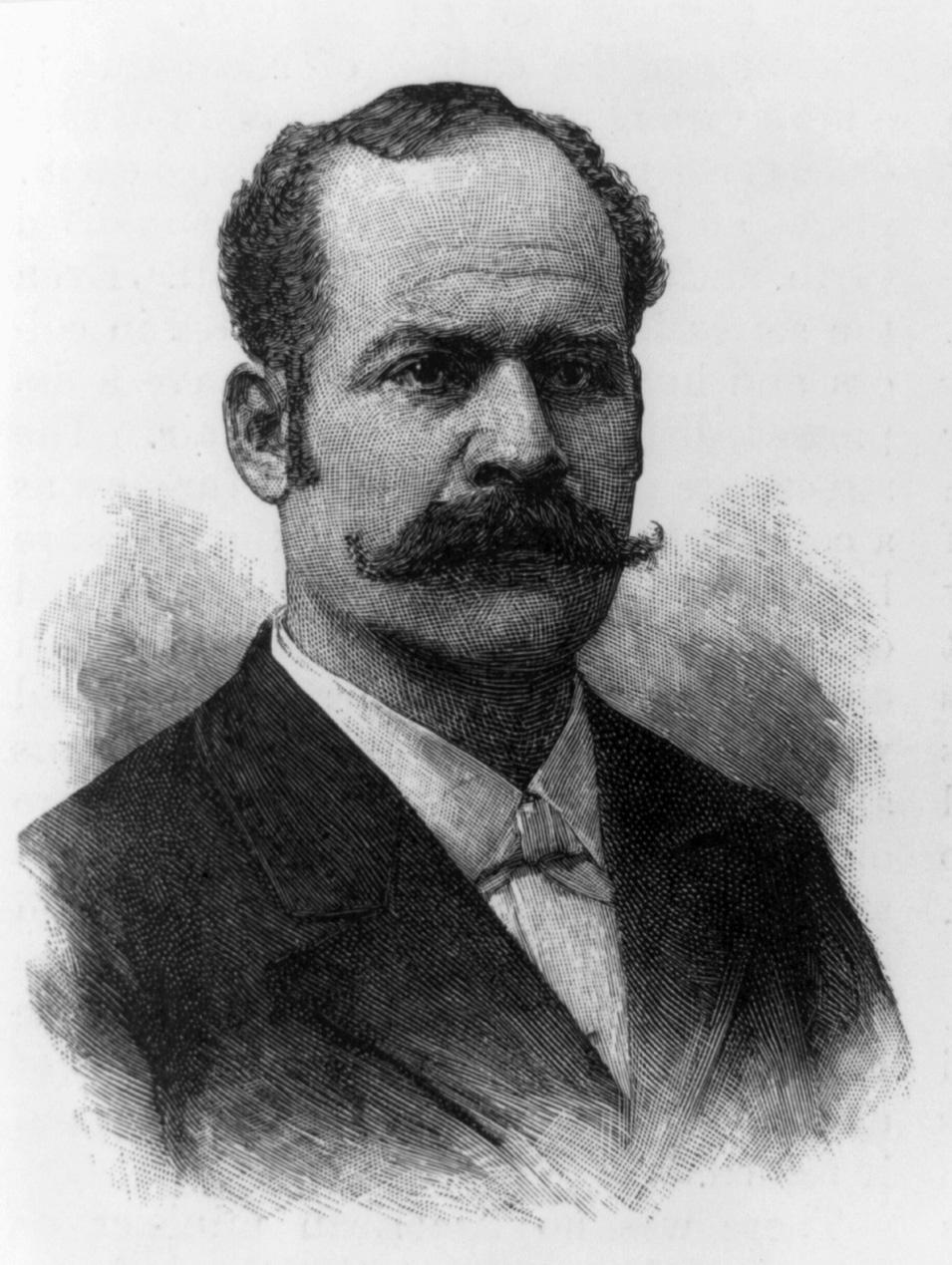

José Santos Zelaya, President of Nicaragua. Illustration in Harper's Weekly, 1895. Public Domain