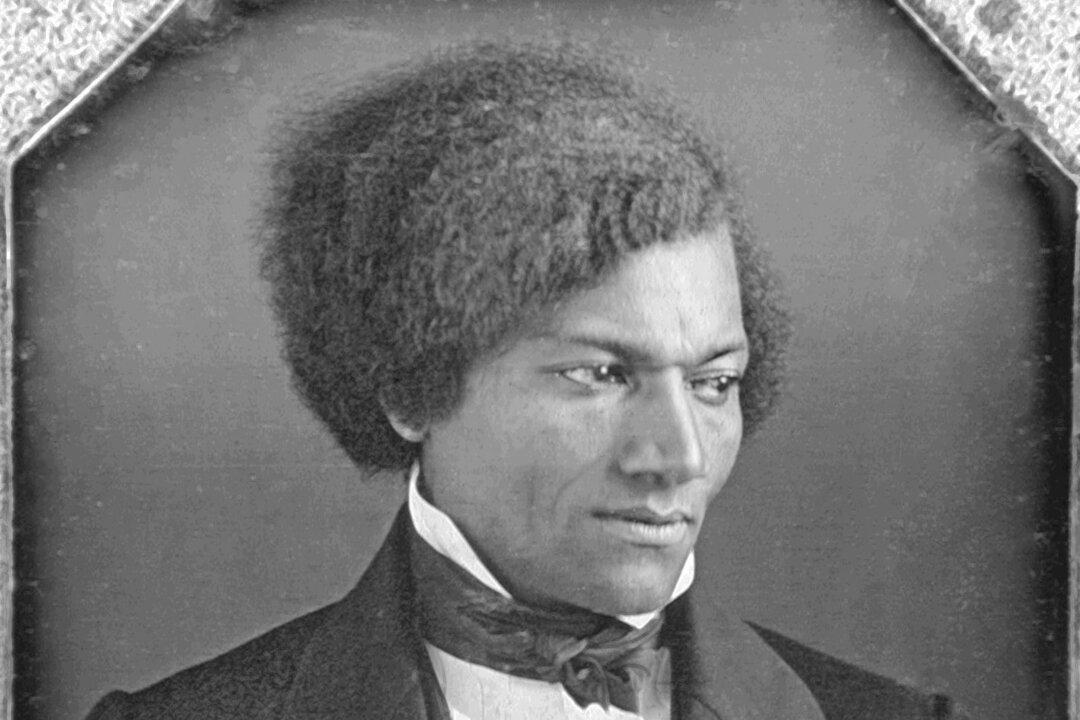

Of Irish heritage, James J. Hill grew up on the Canadian frontier. Despite the loss of vision in his right eye after a hunting accident at age 9, little “Jim” was a savvy fisherman and expert hunter, both with his handmade bow and his rifle. Raised by a Catholic mother and a Baptist father, Hill was educated by Quakers, under whose tutelage he mastered surveying and geometry at a young age. His great love, however, was reading, whether it was Walter Scott’s “Ivanhoe” or the great volumes of Shakespeare kept on the family bookshelf. These humble beginnings belied the fact that, one day, James J. Hill would be known far and wide by the sobriquet “The Empire-Builder” and live in the largest private residence—22 fireplaces, a two-story art gallery, 13 bathrooms, a hundred-foot-long reception hall—in the state of Minnesota.

When Hill was 14, his father died, and the teenager abruptly became his family’s primary earner. Working for a dollar a week as a clerk, he honed his mathematics skills and became acquainted with the world of commerce. As time passed, Hill became fascinated by the prospect of trade with Asia and determined to visit the Far East some day. First, though, he wanted to see the United States, and so, still in his mid-teens, he packed his bags and embarked upon a tour of America’s eastern seaboard, from New York all the way to Savannah, then inland to Chicago and, eventually, St. Paul.