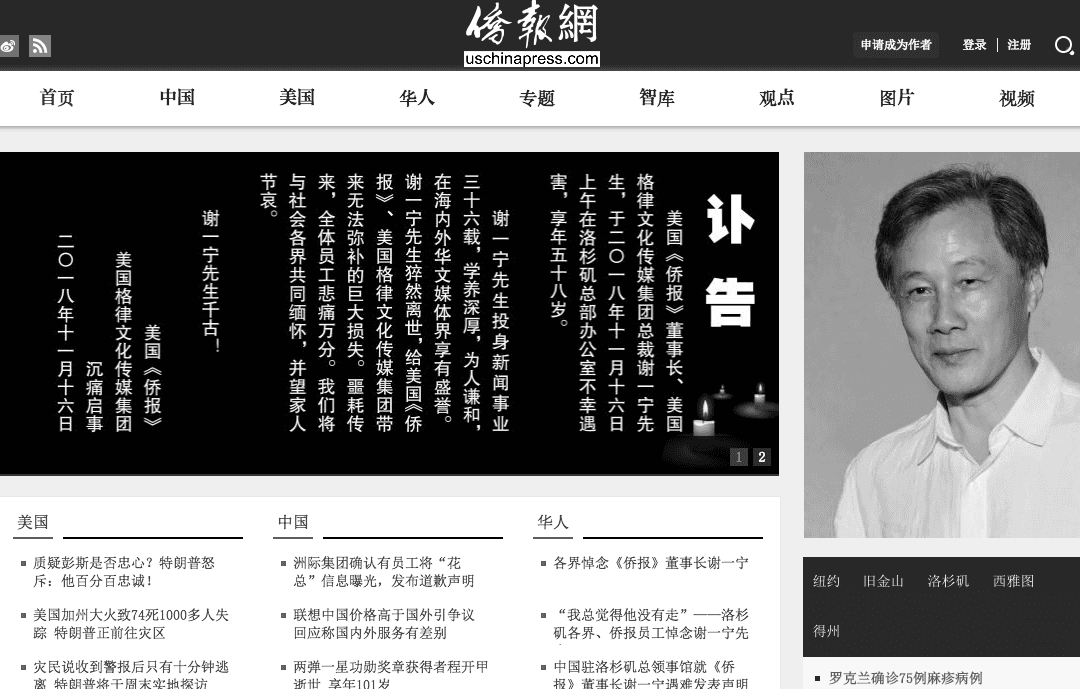

Xie Yining, the founder and chairman of the U.S.-based Chinese-language newspaper China Press, was shot to death inside the publication’s office in Alhambra, California, according to a report by local newspaper San Gabriel Valley Tribune.

After receiving a call on Nov. 16 from a man who said he had been shot, local police found Xie, 58, at the newspaper office, where he was pronounced dead. Police recovered a handgun at the scene and arrested an employee identified as Zhong Qi Chen, 56, on suspicion of murder.

Zhong is currently held on $1 million bail. Police didn’t indicate a motive for the shooting.

Newspaper’s Background

China Press, better known as Qiao Bao in Mandarin Chinese, is a Chinese-language newspaper long known in the U.S. immigrant community for its pro-Beijing views and propensity to repeat Beijing’s propaganda on a wide range of issues.

During the current trade dispute between China and the United States, for example, China Press has run an article advancing Beijing propaganda, such as that the trade dispute was being pressed by President Donald Trump to win Republican votes in the November midterm elections.

Since Beijing launched a nationwide persecution of the spiritual group Falun Gong in 1999, China Press has been among a number of overseas Chinese newspapers that repeated propaganda in mainland China’s state-run media, vilifying the meditation practice and its adherents. Meanwhile, Chinese media often repost China Press articles, such as one titled, “Overseas Chinese in Seattle support China’s sovereignty in the South China Sea,” in July 2016.

Many suspect that the newspaper is actually run by the Chinese regime.

On paper, the newspaper is under the umbrella of Rhythm Media Group, a California-registered firm founded in 2003 with several Chinese-language news outlets, a film production company, and a cultural center in its profile. But Xie’s background and a look into the company’s history indicate that it, in fact, has close ties to Beijing.

On Nov. 18, China Press published an obituary spread about Xie’s death, giving a brief biographic timeline. After graduating from university in 1982, Xie became a reporter for the state-run China News Service. In 1987, Xie became the White House correspondent for the news service. In 1992, he left his position to establish China Press in San Francisco; the newspaper also has editions in Los Angeles and New York.

Notably, the China Press obituary included a statement of condolence from the Chinese consulate office in Los Angeles.

“Under Mr. Xie’s leadership, China Press gave great contributions ... to service overseas Chinese in America,” the statement read.

Xie had attended events organized by the Chinese regime’s Overseas Chinese Affairs Office several times over the years. In April 2016, the office’s official website reposted a media article mentioning Xie’s participation in a press tour of a tech incubator in Jiangsu Province organized for overseas media outlets.