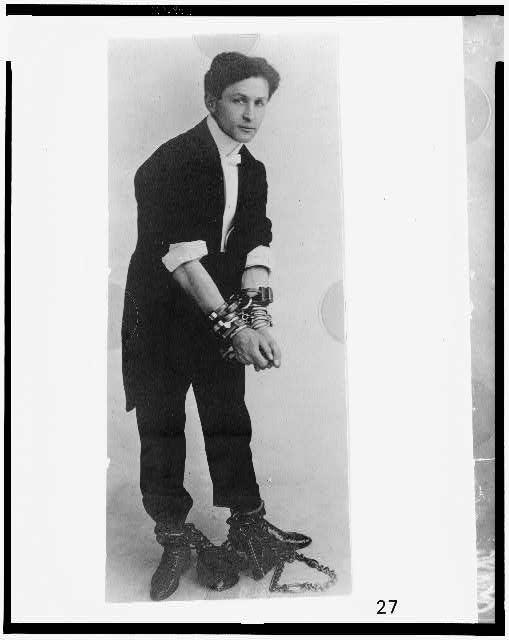

Even today, nearly a century after his death, we say his name. The dog gets out of the yard, or the baby out of the playpen, and someone will say: “That little Houdini!” The name still stands for “magician” the way “Fido” stands for “dog.”

The funny thing is, Houdini wasn’t really a magician. Or rather, after failing as a magician, he reinvented himself in a new role that made him famous: the escape artist.