A pyramid scheme in China has been revealed to have ensnared millions of investors, who have jointly lost 30 billion yuan (about $4.7 billion) in investment capital.

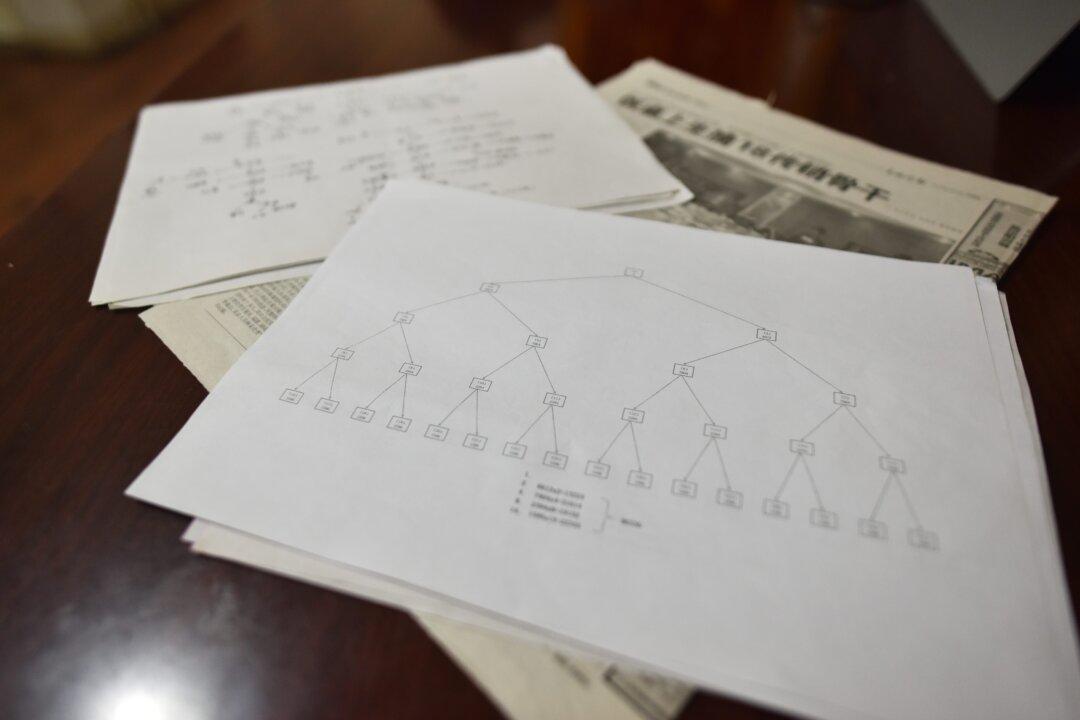

Back in December 2017, Zhang Xiaolei, founder of online platform Qianbao.com, turned himself in to the police, admitting that he had been running a Ponzi scheme since the company’s founding in 2012.