How Trump’s ‘Liberation Day’ Tariffs Are Set to Reshape Global Trade

The president will reveal the long-awaited details of his tariff plan at a White House Rose Garden event, set to take place after stock markets close.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s ‘This Lime-Tree Bower My Prison’

An unfortunate accident led the 18th-century poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge to craft a beautiful ode to nature and friendship.

‘The Penguin Lessons’: A Man, a Bird, and a New Perspective

A teacher comes to a boarding school to escape his past in this entertaining and deeply moving film.

A Heartbreaking, Inspiring Retelling of the Chosin Reservoir Withdrawal

Brutal and graphic, Joseph Wheelan’s ‘The Farthest Valley’ is a necessary work of one of America’s most heroic military moments.

Most Read

Top Stories

4 Takeaways From April 1 Elections in Florida, Wisconsin

Voters filled two House seats, a judicial seat in a state Supreme Court, and answered a ballot question, all with implications for the Trump agenda.

US Manufacturing Sector Contracted in March, Report Says

The Trump administration is set to announce reciprocal tariffs on trade partners to boost domestic manufacturing.

Trump Admin Ordered to Restore Legal Aid for Unaccompanied Minors

About 26,000 illegal immigrant children who entered the United States without a parent or guardian currently receive federally funded legal representation.

What to Expect From Trump’s Global Tariffs

Experts say the road to reciprocity will be bumpy but necessary. One, in particular, expects to see early signs of an economic boom before the 2026 midterms.

▶Whistleblower Reveals Far Reaching CCP Influence in UN: Emma Reilly

Emma Reilly worked as a human rights lawyer at the United Nations and was fired after blowing the whistle and revealing a UN secret policy of assisting China.

Val Kilmer, Star of ‘Top Gun’ and ‘Batman,’ Dies at 65

The actor died from pneumonia, his family confirmed.

Danish Prime Minister to Visit Greenland Amid US Interest In the Territory

Mette Frederiksen’s visit comes on the heels of a trip to the Arctic territory by U.S. Vice President JD Vance, who accused Copenhagen of failing Greenlanders.

Trump Says Agency Heads Will Work With DOGE After Elon Musk Leaves

The president on Monday provided an update on DOGE and Musk.

Trump Admin Says Encounters at US–Mexico Border Dropped to Lowest Levels Ever in March

March encounters represent a sharp drop from the same month under the Biden administration, the White House said.

German Foreign Minister Says Talks Over Truce in Ukraine Have Hit ‘Deadlock’

President Volodymyr Zelenskyy called for tougher sanctions on Moscow and said, ‘I believe the Russians are breaking the promises they made to America.’

Witnesses Tell House Task Force to Reinvestigate JFK Assassination

Award-winning filmmaker Oliver Stone led a panel of experts testifying about the need for transparency from the federal government.

▶Shen Yun, a Journey to China Before Communism, Is Wonderful: Rockford Audience

Shen Yun Performing Arts transported the audience at the Coronado Theatre in Rockford, Illinois, on a breathtaking journey through 5,000 years of Chinese civili

Wisconsin Votes to Enshrine Voter Photo ID Law in State Constitution

Voter ID is already required by law in Wisconsin, but adding it to the state constitution makes it harder to change in future.

Judge Blocks Trump Admin From Firing Federal Employees on Probation in 19 States

Judge James Bredar found the administration likely broke laws regulating en masse terminations of government employees.

What to Know About Trump’s Order on Election Integrity

The order requires proof of citizenship to register, cracks down on noncitizen voting, and calls for a review of voting machines, among other measures.

Trump Strikes Deal With Law Firm That Partners With Doug Emhoff

This marks the third law firm to reach an agreement with Trump who has recently suspended security clearances for lawyers from several other firms.

Sen. Gallego Announces Blanket Hold on Veterans Affairs Nominees to Protest Planned Staff Cuts

Last month, Veterans Affairs Secretary Doug Collins confirmed he is seeking to reduce the department’s workforce back to its 2019 levels.

Tracking Trump’s High Level Appointments, Senate Confirmations

The Senate is undertaking the confirmation process for the president’s new administration.

Crawford Defeats Musk-Backed Rival to Preserve Liberal Majority on Wisconsin Supreme Court

The outcome continues liberal momentum in state judicial elections despite Trump’s popular vote victory in 2024.

Israel Eliminates Tariffs on US Imports Ahead of Trump’s ‘Liberation Day’

Israeli Finance Minister who has signed the order, said the decision aims to safeguard Israel’s economy and strengthen international relations.

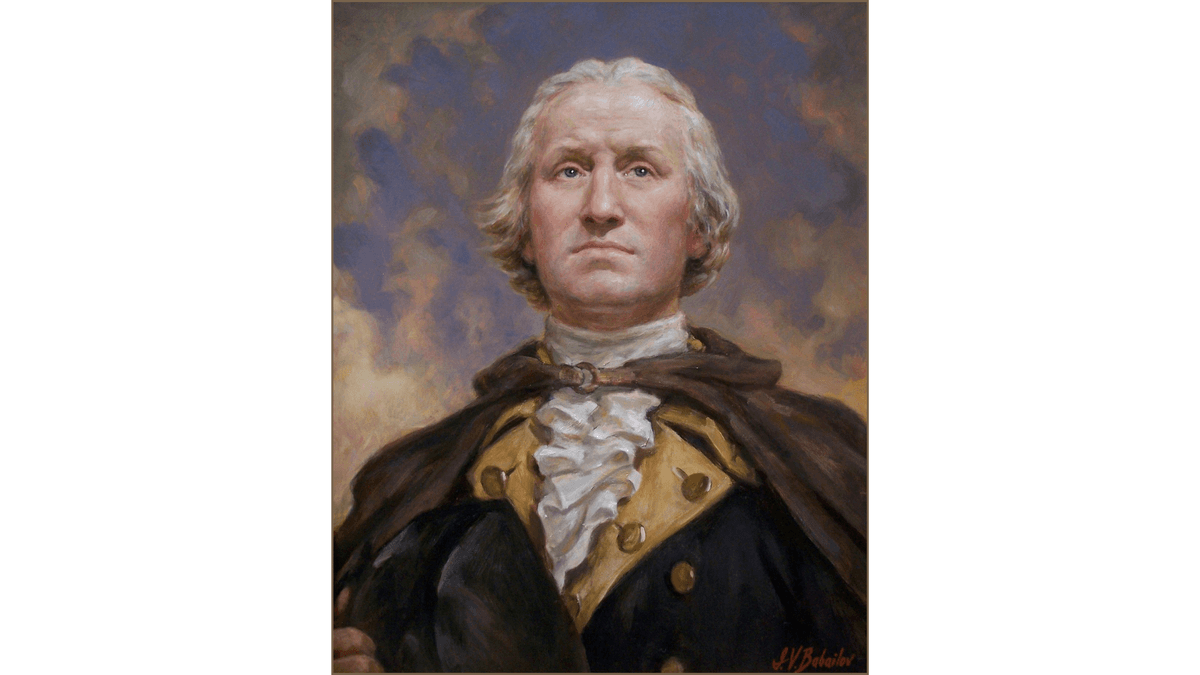

When George Washington Calmed a Mutiny

In this first article of the series “When Character Counted,” we visit a moment when a pair of spectacles helped save the American experiment of democracy.

Special Coverage

Special Coverage

![[LIVE NOW] ‘Liberation Day’ Tariffs Begin; Trump Vows to ‘Fight It Out’ | Live With Josh](https://www.theepochtimes.com/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fimg.theepochtimes.com%2Fassets%2Fuploads%2F2025%2F04%2F01%2Fid5835188-040225_REC-600x338.jpg&w=1200&q=75)