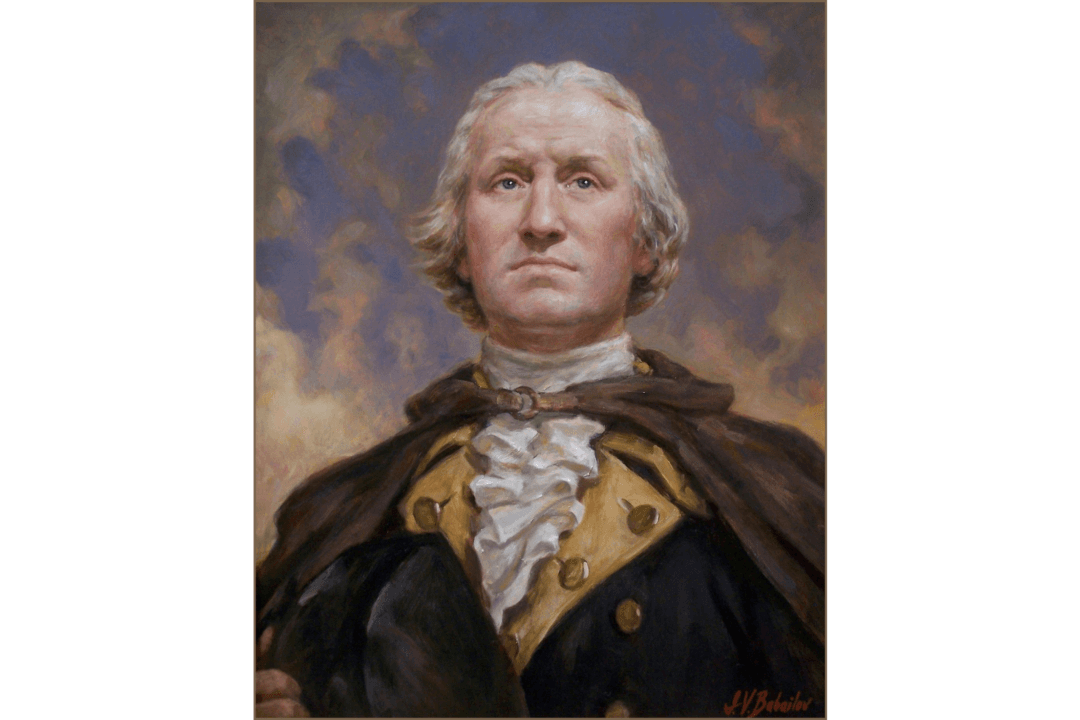

It was mid-March 1783 in Newburgh, New York, but mutiny, not spring, was in the air.

Dissatisfaction and anger had reached the breaking point in the Continental Army encampment. With the fighting essentially ended and peace with Great Britain impending, the Confederation Congress in Philadelphia was dithering on paying the soldiers and officers, many of whom hadn’t seen a penny in months.