The world’s last-known commercial fore-edge painter shares the secrets of his mesmerizing “vanishing” images, painted between the page edges of books, to help keep the magic of his dying craft alive.

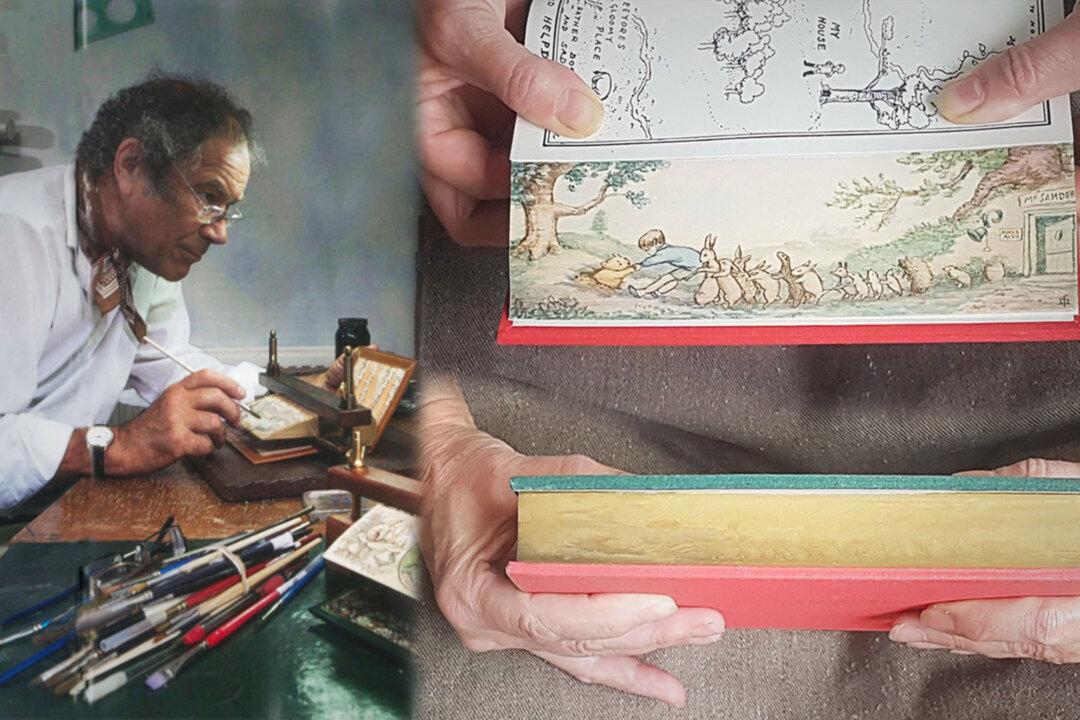

London-born vanishing fore-edge painter Martin Frost paints on the page edges of gold-gilded books. The pages are fanned to reveal his delicate handiwork. Today, Frost, 72, lives in the seaside town of Worthing in southern England and works from home in his painting and book-binding studio.