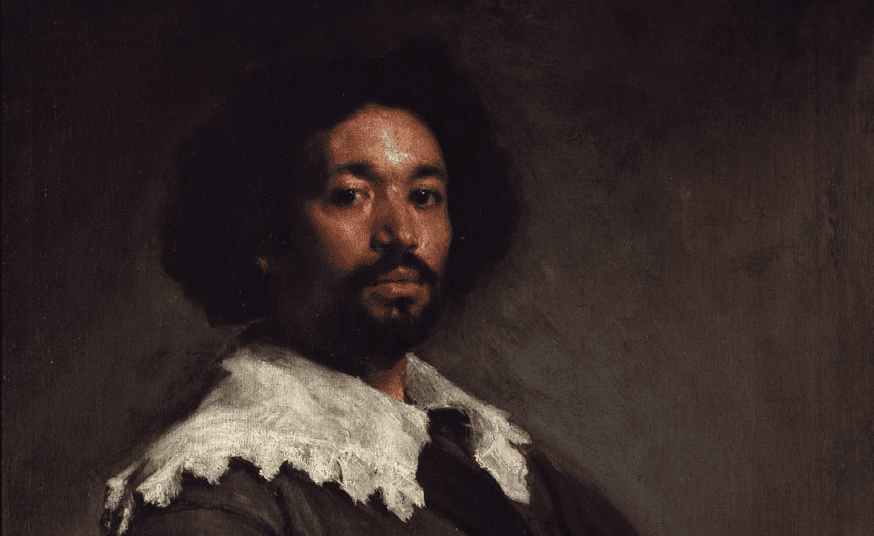

When Diego Velázquez’s “Juan de Pareja” was acquired at auction by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1971 for $5.5 million, it set a new record for the amount ever paid for a painting.

The price reflected the work’s recognized cultural importance by this prestigious institution. In its honorary publication “Juan de Pareja by Velázquez: An Appreciation of the Portrait,” Curator-in-Chief Theodore Rousseau states that the work is “among the most beautiful, most living portraits ever painted.”

Considering the accolades, it is surprising the scarcity of visitors to gallery 610 at the Met. In fact, the room is quite empty most of the time.

Historically, interest in Velázquez’s art has been cyclical and often limited to aesthetic circles. Widely esteemed by the end of his lifetime, Velázquez’s reputation waned until the second half of the 19th century. Even then, enthusiasm for the Spaniard’s art was limited to a small group of life-size portrait painters such as Carolus-Duran and John Singer Sargent.

There is no doubt the painting is a masterpiece. Created during the master’s second trip to Italy (1649–1651), it was a “warm-up” for the important commission of Pope Innocent X.

The picture garnered universal acclaim after it was shown publicly in the portico of the Pantheon in Rome. So lifelike was the portrait, according to the biographer Antonio Palomino, that it was confused with reality.

In true virtuoso fashion, all the painterly conceits—color, value, broken brushwork, and soft edges—are perfectly orchestrated not in stylistic affectation but to express the experience of natural perception.

Typically used to describe the Met’s picture are the adjectives “living,” “real,” and “truthful.” These are the fruit of the artist’s research where the mechanics of human vision intersect with the poetry of picture making. Perhaps Velázquez’s goal was to remove the barrier between the artwork and audience. Regardless, the result was revolutionary as it subjected the existing canons of representation to the visceral reality of retinal observation.

R.A.M. Stevenson explains this concept in his 1895 book, “The Art of Velázquez.” More than a simple art historian, Stevenson was a painter who had studied under Carolus-Duran with Sargent.

Stevenson describes Velázquez as the first exemplary exponent of “impressionism.” Intending more than the post facto description of the French school of painting of the latter 19th century, impressionism is the fruition of ideas that were germinated in the Renaissance by artists like Titian.