When visiting the reorganized Vatican Museum in Rome, tourists now pass through the galleries of antique art on their pilgrimage to see the Sistine ceiling. The vast number of delicately carved marble sculptures, busts, and fragments only add to their anonymity.

Silent and colorless, their effect en masse is almost monolithic and impenetrable. As a result, many visitors pass through in awe of these stone memories yet never pause to study any piece in its particular.

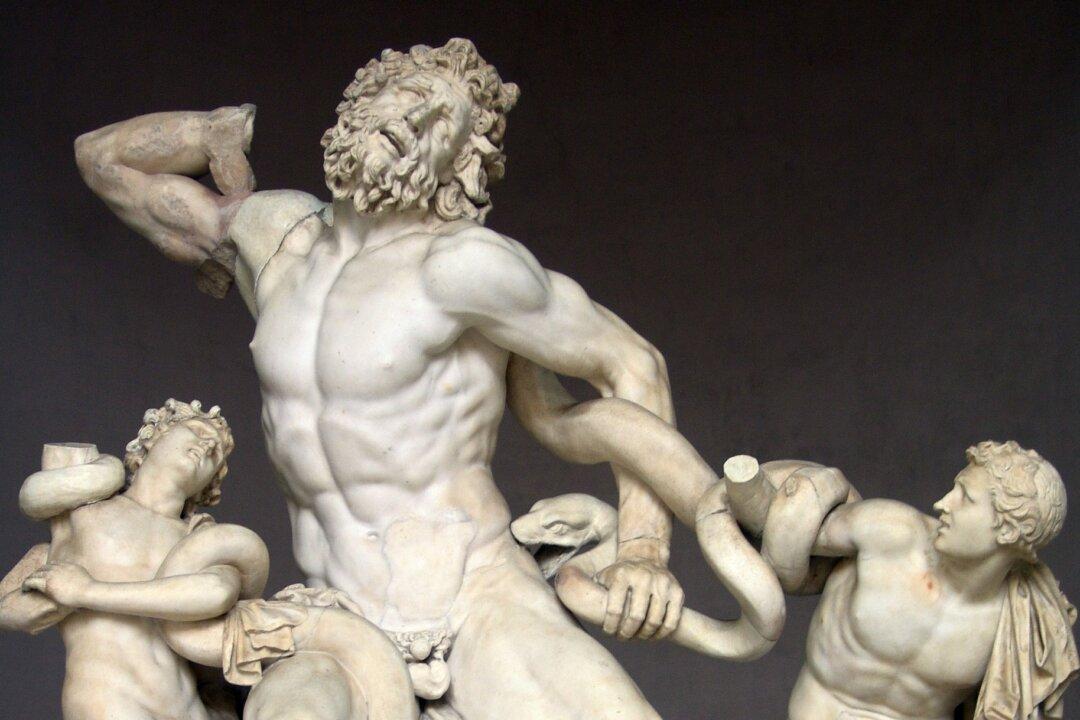

However, upon entering the Octagonal Court, it is almost impossible not to stop before Laocoön Group. The canonical tranquil composure of the surrounding sculptures only highlights the dynamic energy of this magnificent work.

Punished by the Gods for warning the Trojans about the danger of accepting gifts from Greeks, the priest of Apollo and his sons are in the act of being killed by giant serpents.

Pliny the Elder cites this work as one of the best from antiquity and was displayed in the palace of Emperor Titus. He names the three sculptors of the piece as: Hagesandros, Polydoros and Athenodoros of Rhodes. He even boasts that it was carved from a single block of marble. But even our Roman source is not infallible.

The Vatican group consists of different blocks expertly pieced together. Recent scholarship has revealed that the sculpture is probably an Imperial era copy (thus the date of 26 B.C.) of a lost Pergamon school (c. 240-133 B.C.) original. (Smith, 2005)

But Pliny the Elder’s mistake is understandable. Copies are by definition derivative and usually inferior. However, it is difficult to imagine improving upon this masterpiece. The composition is powerful and complete. The dramatic tension, both emotive and anatomical, is magnetizing.

Lost for over a 1,000 years, Laocoön was rediscovered in 1506 and exerted an enormous influence on the art of the Italian Renaissance.

Architect Giuliano da Sangallo and Michelangelo were summoned to the excavation site on the Esquiline Hill where Giuliano immediately identified the sculpture. The young Florentine sculptor had recently finished his colossal David and was in Rome to begin work on Pope Julius II’s tomb. (Barkan, 1999) His fateful encounter with the Laocoön transformed his art almost completely. The trademark qualities of his style by which he is best known today: anatomical, muscular, male nudes in dynamic twisting poses are seen right away in both his painting and sculpture.

But, the technical bravura of the three sculptors from Rhodes had set a new benchmark by which all following sculptors would have to judge themselves. One cannot help but imagine that Michelangelo felt this challenge and perhaps was even intimidated. He was, after all, recognized by his contemporaries as the greatest living sculptor in Italy, an equal of the ancients. Yet he had never carved a statue as complicated as the Laocoön. In the end he never did.

In the 58 remaining years of his career, Michelangelo only fully completed a handful of sculptures. Even those were not brought to the level of finish of his early works, like the Pieta and the David. Most of his large marble figures were to be abandoned and left incomplete.

With today’s modern views about the infallibility of genius, chance and error are mistaken for willful intent. I feel that his confidence was shaken but what little Michelangelo lost in sculpture he regained in the mastery of fresco painting. In 1508 the Sistine ceiling was begun. When it was completed he had succeeded in realizing one of the most important iconic images in the last 1,500 years: God creating Adam.

So the next time on your way to see the Sistine ceiling spend some time in front of a powerful sculpture of death and reflect upon how it inspired such a beautiful painting of spiritual birth. That is the power of art.

Matthew James Collins is an American artist based in Florence, Italy. He creates works in oil, fresco, marble, and bronze. His website is matthewjamescollins.com

Sources cited:

Barkan, Leonard, Yale University Press, 1999, Unearthing the Past, Archaeology and Aesthetics in the Making of Renaissance Culture

Smith, R.R.R., Thames and Hudson, Ltd. 2005, Hellenistic Sculpture