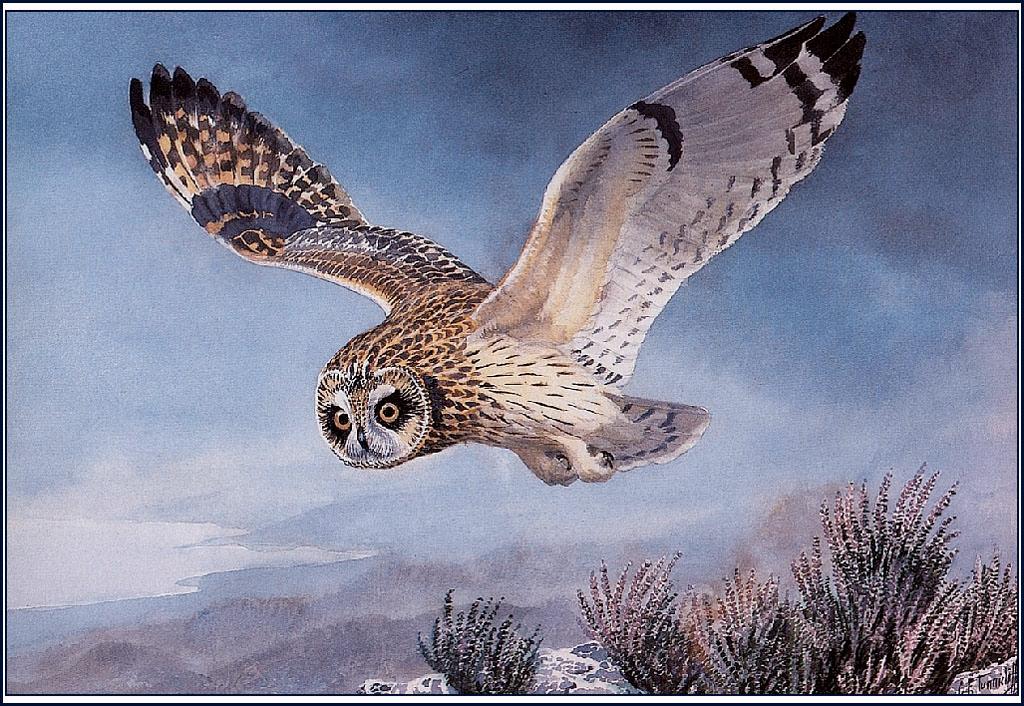

I spent a good portion of time reading this book in the serenity of our backyard gazebo in Virginia: soft breezes, wind chimes tinkling, and the occasional flurry of feisty hummingbirds at the feeders. They are such tiny and tenacious little birds: territorial, adept at aerial acrobatics, and incredibly fast. Owls share some of their skills, but they are clearly their own breed of bird.

To date, we have not had any owls fly through our yard—that I am aware of—but then, they are predominantly night creatures and have their own set of unique characteristics.