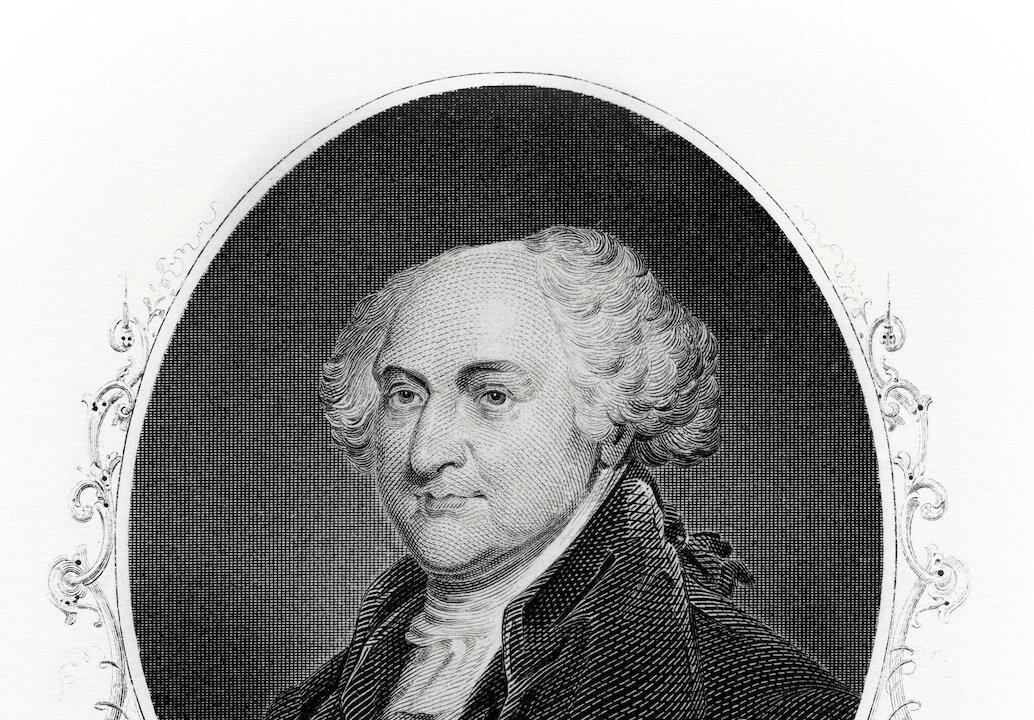

Benjamin Franklin ranks among the most popular of the Founding Fathers, and for good reason: He was a larger-than-life scientist, inventor, diplomat, and above all, cunning politician and staunch advocate for the right of Americans to cast off British shackles and chart their own course. But beyond his inventions, his advocacy as delegate to the Second Continental Congress, or his famous and quotable wit, one achievement affects the daily lives of modern Americans more than any other: as postmaster general of the Colonies and, later, the first postmaster general of a fledgling United States of America. By revolutionizing the system of mail delivery, he, perhaps more than any other, united the men and women of the Thirteen Colonies through the power of the written letter.

In 1737, at a vibrant 31 years of age, Benjamin Franklin was appointed postmaster of the city of Philadelphia by the deputy postmaster general of America. Franklin had learned firsthand the power of the office when his newspaper ran afoul of the previous postmaster general of Philadelphia, who, as publisher of a rival paper, banned Franklin’s paper from distribution. Franklin immediately set about reforming the postal system of his beloved home city but yearned for higher things: the opportunity to guide the entire postal system of the Colonies, from Georgia to Massachusetts. He rose through the ranks, earning the respect of the postmaster general of America, who made him comptroller of not just Philadelphia but also of the surrounding postal offices. In 1753, he realized his ambitions, and the Crown appointed him joint postmaster general of America with William Hunter of Virginia.