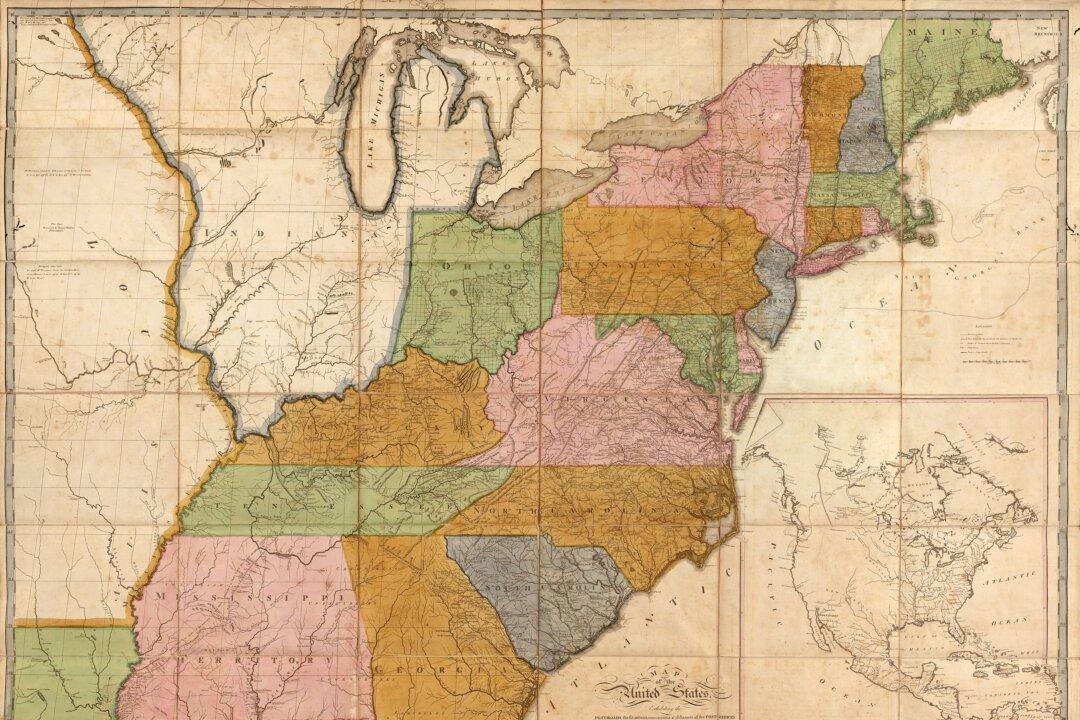

Across New England, snow fell early in the day on March 5, 1770. In Boston, a single sentry, Private Hugh White, grenadier of the 29th Regiment of Foot, stood watch at the Customs House, a soldier of one of the two regiments of His Majesty’s Army remaining in the city to keep the peace and enforce the royal taxes. As night fell, passersby cast dark looks at the lone, red-clad figure bundled against the wind. Public opinion, already soured, had slumped to a new low when, just 11 days before, a customs official fired into an unruly crowd, killing 11-year-old Christopher Seider. The boy’s funeral drew more than a thousand angry Bostonians.

With tensions already at the boiling point, all it took was a single spark. At about 9 in the evening, well after dark, a shop boy jeered at Private White, who left his post to reprimand the boy. The two exchanged words; the grenadier struck the boy with his musket. Soon, a swirling mass of men and boys—sailors, shop boys, and dockworkers—surrounded the sentry, who retreated up the steps. Church bells rang out, summoning more to the crowd. Six additional grenadiers arrived to reinforce Private White, accompanied by their commanding officer, Captain Thomas Preston. The crowd grew, shouting, jeering, and hurling ice shards, snowballs, and cudgels. One of the grenadiers, struck by a thrown object, fell and dropped his weapon before angrily rising and firing into the crowd. Shortly thereafter, without orders, the remaining soldiers discharged their muskets. When the smoke cleared, three men lay dead. Two more later died of their wounds.