Virginia Woolf asks us—we hear her own voice, by way of a BBC recording—“How can we combine the old words in new orders so that they survive, so that they create beauty, so that they tell the truth?”

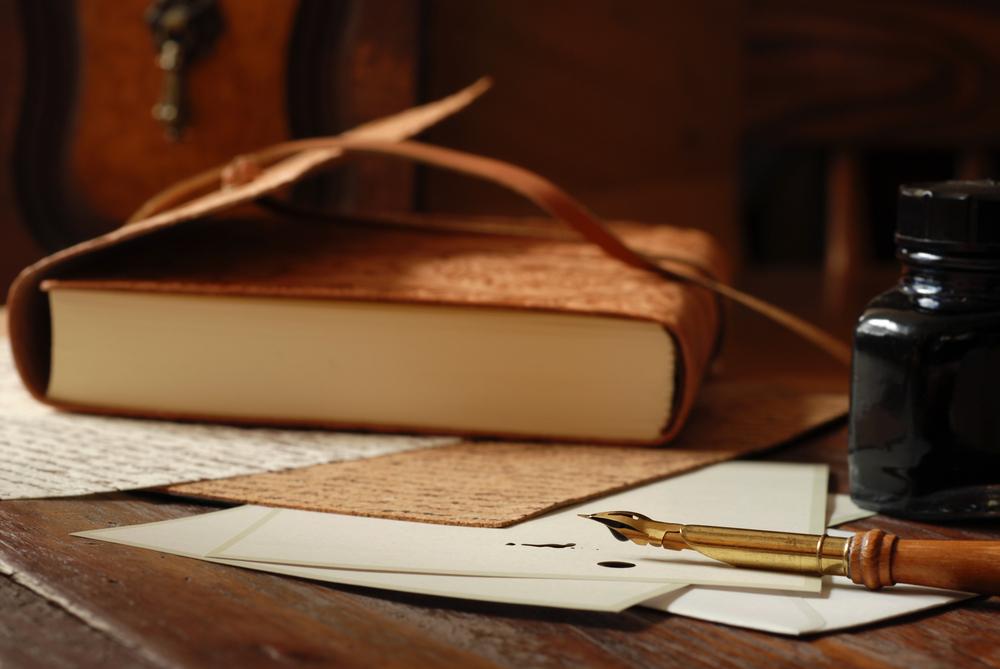

This was Woolf’s life question, her life quest, the catalyst of her genius. She struggled with it, like Jacob struggled with the angel, and she would not let go until the true and the beautiful, in one way or another, blessed her. “When I write, I always, always tell the truth,” she admonished a friend who suggested that she might do otherwise. In her letters, diaries, and fiction, the struggle never ends.