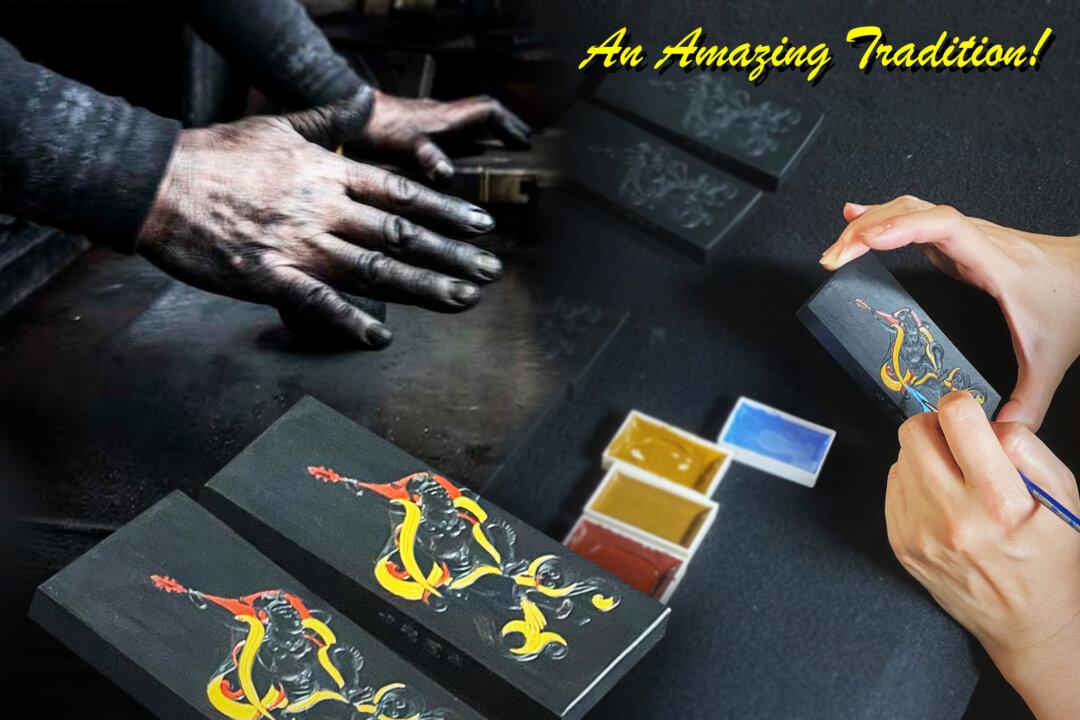

Craftsmen at an almost 450-year-old Japanese ink shop are using their bare hands to knead dough, made from fine soot and animal glue, into high-quality, 200-gram calligraphy ink bars that retail for over $1,000 a bar.

Kobaien in Nara, Japan, was established in 1577 and makes sumi ink to this day through “earthenware smoke collection,” a traditional method, influenced by Chinese ink craftsmen, that has remained unchanged for over four centuries. Kobaien believes that by “valuing the traditional method and sticking to the old-fashioned way of production,” they can continue to produce the highest quality ink.