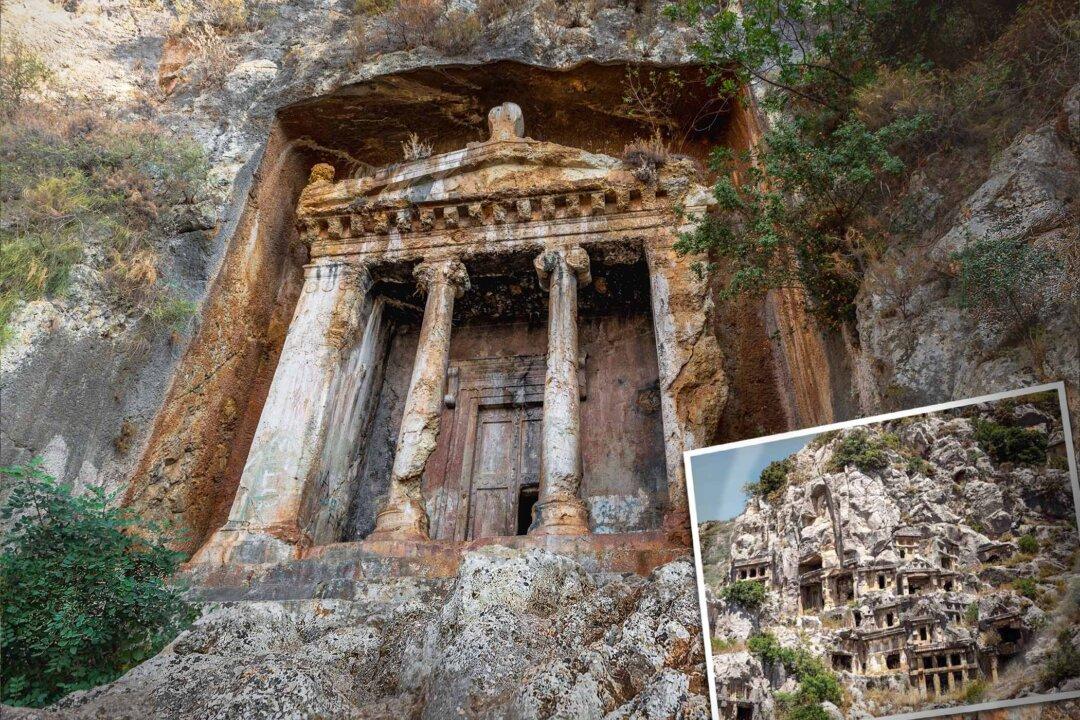

Ruined cities were left behind by the ancient Greeks whose wisdom became the basis of Western society; museums have been filled with artifacts attesting to the great genius and beauty of their civilization; yet almost nothing is known of another ancient Mediterranean people and their culture: the Lycians.

Only a few fascinating stone ruins from as early as the 5th century B.C. attest to their elusive existence.