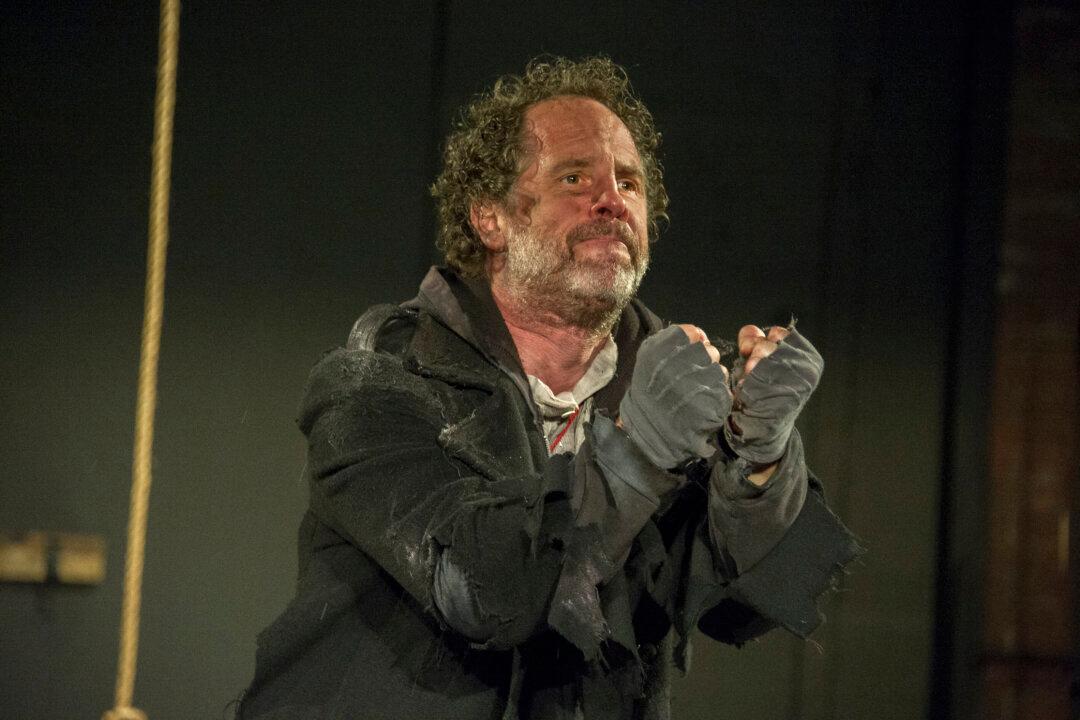

For the second time this week, I’ve seen a black-box theater/one-man show, featuring a singular, titanic, wrecking-crew of a howling, flailing, roaring, crawling, running around, climbing up stuff, swinging from the rafters, sweating, moaning, copious-Cornish-accented-cursing creature of showbiz.

That’s “Albatross,” an interpretation of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s famous poem, “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.” And here we have the titular Mariner, traveling around, telling his tale, in real time.

The spirits loved the bird, who loved this man. And now there's beaucoup karma to pay.