Into this season of pandemic, quarantine, and hardship comes Passover.

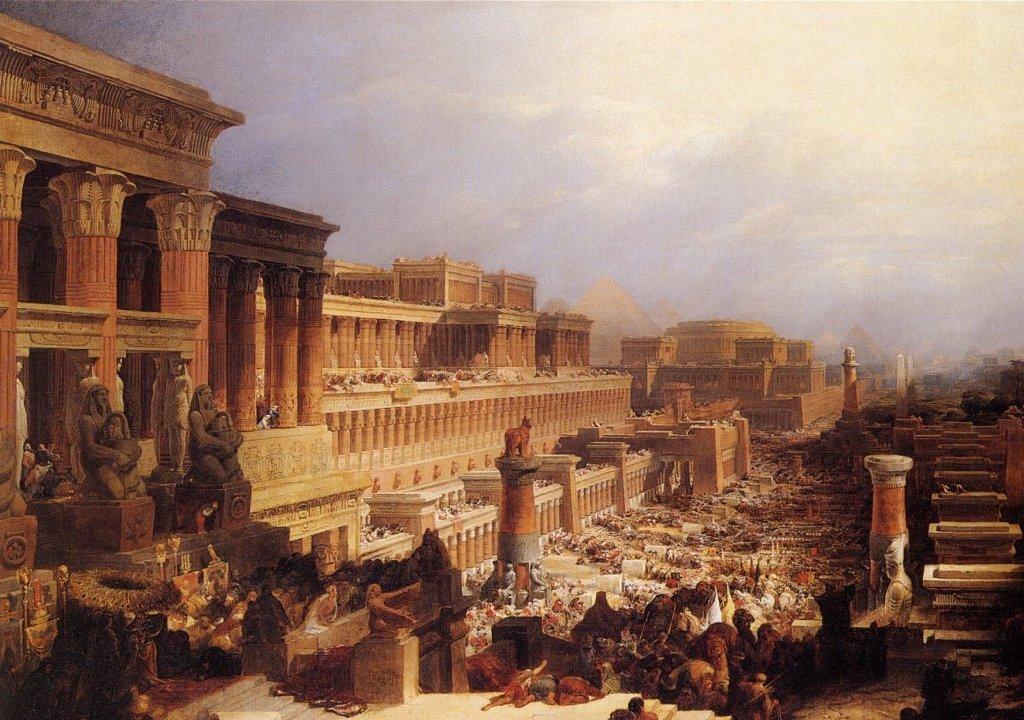

The Jewish celebration of Passover derives from Exodus 12 of the Bible, when the last of 10 plagues visited upon the Egyptians brings about the death of firstborn sons in Egyptian households. To ensure the safety of the Israelites, God commands Moses and Aaron to tell the Hebrews to collect the blood of the lambs they have sacrificed and to smear that blood on the doorframes of the houses and also to eat the lambs.