How can we become better people? What does it take to discard vice and embrace virtue? What’s the role of faith and reason in the pursuit of goodness?

These questions have interested humans for millennia. According to For the Greek philosopher Plato and the Russian author Fyodor Dostoevsky, attempts to answer these questions should consider the nature of the human soul.

The Soul in Three Parts

Plato (circa 427–348 B.C.) revolutionized the Western intellectual tradition with a series of dialogues that feature his mentor Socrates. Among them is the “Gorgias,” which explores the relationship between rhetoric, freedom, and justice.

“The School of Athens” fresco by Renaissance artist Raphael depicting the Platonic Academy, a famous school in ancient Athens founded by the philosopher Plato in the early 4th century B.C. In the center are Plato and Aristotle, in discussion. Public Domain

Story continues below advertisement

Plato thought the soul has three parts, each represented by one of Socrates’s three interlocutors. The first is the acclaimed rhetorician Gorgias, who was also a historical figure. His participation in the dialogue represents reason. However, readers quickly discover that Gorgias’s “rationality” is more like shrewdness.

His mastery of language allows him “to make the weaker argument stronger,” which he says is the most reliable way to exert power over others and obtain freedom. Gorgias isn’t committed to truth or justice. Rather, he wants to use his rhetorical prowess to deceive others into believing whatever he says. For someone as astute as he is, any moral outlook is equally justifiable, and therefore equally justified.

The second interlocutor is one of Gorgias’s pupils, the impatient and impulsive Polus, who represents the passionate part of the soul. Polus is quick to defend his mentor, often feels slighted by Socrates’s comments, and issues angry objections against what he perceives as intrusive questioning. He has no time for talk or games. He wants answers, lest anger take ahold of him.

Socrates’s last interlocutor is Callicles, who represents the appetite. For Plato, the “appetite” is the base urge for food, sex, and the like. Callicles unashamedly articulates a worldview based on power and the dominance of the strong. His views, which inspired such radical thinkers as Friedrich Nietzsche, are an ancient version of the “survival of the fittest.”

As Callicles says, “superior” people allow their “appetites to get as large as possible and not restrain them.” They should apply their wit and courage to satisfy whatever desires they happen to have at any given time, be they for food or domination. The unbridled pursuit of pleasure and power: that is Callicles’s way.

Story continues below advertisement

Detail of "The Feast of the Gods," 1514 and 1529, by Giovanni Bellini and Titian. Oil on canvas. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Public Domain

Plato thought that reason, passion, and the appetite must work together under the direction of reason. An ordered soul makes a person stable, but the soul can only be ordered if it follows reason’s guide.

“Reason” here doesn’t mean the malicious shrewdness of a Gorgias, but rather the honest application of logic that Socrates represents. The philosopher embodies genuine rational inquiry, which unfolds in dialogue and doesn’t seek to dominate others. He’s also passionate. He pursues truth indefatigably and isn’t afraid to engage his competitive interlocutors with vigor, so long as they agree to seek the truth.

Lastly, Socrates knows how to regulate his appetites. He compares Callicles to an owner of “leaky jars” who is “compelled to fill them constantly, all night and day, or else suffer extreme distress.” Unlike one who seeks what’s bound to vanish, Socrates is stable, like a jar that’s always full.

Story continues below advertisement

Terracotta Hadra hydria from the 3rd century B.C. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Plato saw Callicles' mindset as insatiable and unsustainable. Public Domain

The “Gorgias” has been incredibly influential throughout the Western tradition, in part because it illustrates common human personality types. Over 2,200 years later, the Russian author Fyodor Dostoevsky revisited Plato’s themes in “The Brothers Karamazov,” which offers readers even more detailed examples of what it means to “order the soul.”

The Soul of the Karamazov Family

The late Yale Professor Robert Jackson suggested that at the heart of Dostoevsky’s “artistic and philosophical consciousness” was “a central concern with man, the view of him as an enigma, and the thought that to be a man one must have an active interest in the human condition.” Dostoevsky described his method as a search to resolve this enigma: “I go into the depths and, analyzing atom by atom, I seek out the whole.”

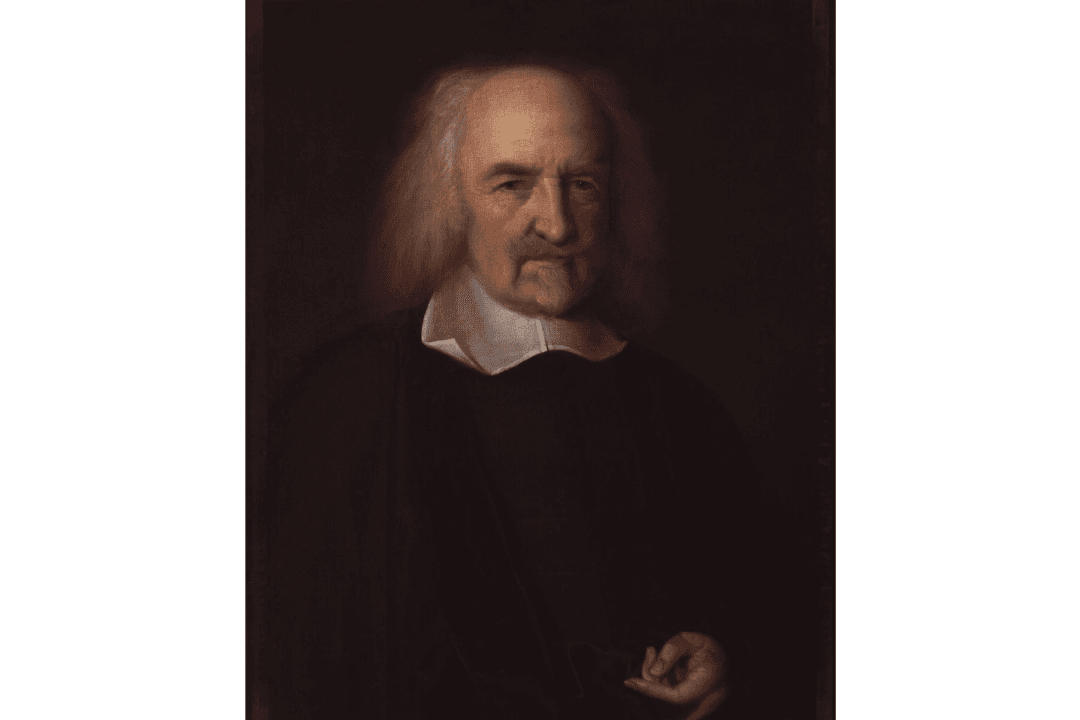

Portrait of Feodor Dostoevsky, 1872, by Vasili Perovby. Tretyakov Gallery. Public Domain

Published between 1879 and 1880, “The Brothers Karamazov” is a perfect example of Dostoevsky’s penetrating insights into the human psyche. It’s been described as a “theological drama” for its reflections on doubt, reason, free will, and a host of other philosophical issues. These reflections unfold through the trials and tribulations of the Karamazov family: Fyodor, the father, and his three sons, Dmitri, Ivan, and Alyosha.

Story continues below advertisement

Fyodor is self-indulgent and hedonistic. He avoids his responsibilities as a father and is always looking for his next drink. After his murder, the prosecutor describes Fyodor almost exactly like Socrates describes Callicles:

“He saw nothing in life but sensual pleasure, and he brought his children up to be the same. … He was an example of everything that is opposed to civic duty, of the most complete and malignant individualism.”

Fyodor’s eldest son, Dmitri, is as hedonistic as his father. He’s also irascible and irate. His combative spirit is easily stirred, and his explosive anger often prevents him from reasoning about the best course of action. In this sense, Dmitri displays the same spiritedness readers find in Polus. But he also displays a self-awareness not found in the “Gorgias.” Dmitri often knows where he’s gone wrong. This recognition inspires one of the most incisive lines in the book: “Beauty is mysterious as well as terrible. God and the devil are fighting there and the battlefield is the heart of man.”

"Old Man Seated," between circa 1630 and circa 1633, by Rembrandt. The numbing effects of alcohol in the 3rd century B.C. were just as potent as in the 17th century, when Rembrandt sketched a man under the spell of hard liquor. Public Domain

Story continues below advertisement

If Dmitri is often swept by his emotions at the expense of reason, Ivan, the middle Karamazov, is excessively rational. His defining trait is the cold aloofness with which he denies God’s existence. As the prize-winning biographer of Dostoevsky, Joseph Frank, noted, Ivan’s inner debate is “between his recognition of the moral sublimity of the Christian ideal and his outrage against a universe of pain and suffering.”

Like Gorgias, Ivan’s reasoning is incisive and far-reaching. But his hyper-rationality erodes his moral foundation, preventing him from applying himself towards goodness. As Ivan himself realizes, “intelligence squirms and hides itself. Intelligence is unprincipled.” He’s Gorgias taken to the extreme. As mistaken as he is, Gorgias uses reason for a clear purpose: to gain money and influence. Ivan’s purpose is less defined. His relentless skepticism eventually spirals into existential despair, showing readers the frightening inadequacy of untrammeled unbelief.

If Socrates is Plato’s exemplar of a unified soul, who’s Dostoevsky’s?

Faith, Love, and Compassion

Alyosha is the youngest Karamazov brother, and his devoutness contrasts sharply with Ivan’s atheism. Alyosha is undoubtedly intelligent, but overpowering logic isn’t his forte. A novice in a Russian Orthodox monastery, he sees life through a spiritual lens. He embraces God not through reason, but through faith, reflected in his belief in humanity’s innate goodness.

Altar of Holy Epiphany Russian Orthodox Church Boston. Alyosha's belief in Christianity, expressed through Russian Orthodoxy, transforms his character when he undergoes trials in "The Brothers Karamazov." EgorovaSvetlana/CC BY-SA 4.0

Story continues below advertisement

Alyosha’s piety, however, is tested by interactions with fraught and overwhelming personalities, including his own family members. The young Karamazov’s composure sets him apart from his brother Dmitri. Alyosha is passionate, but, like Socrates, he never lets emotions get the best of him. Compassion and gentle charisma are his greatest qualities, which make him the most endearing character in the novel.

Even though Socrates uses reason differently from Gorgias, his signature move is still rational inquiry. Unlike him, Alyosha persuades by example. The novel concludes with the funeral of the young Ilyusha, the son of a military officer who was once assaulted by Dmitri. During the ceremony, Alyosha exhorts those present to remember the deceased boy and cherish the love they felt for one another: “let us remember how good it was once here, when we were all together, united by a good and kind feeling which made us, for the time we were loving that poor boy, better perhaps than we are.”

N.P. Alexeev as Alyosha Karamazov in the 1969 movie "The Brothers Karamazov." Alexander Alexeev/CC BY-SA 4.0

However “bad we may become,” Alyosha says, let’s “recall how we buried Ilyusha, how we loved him in his last days, and how we have been talking like friends all together.” The best aspect of our nature is disclosed in loving communion with fellow human beings.

The Struggle of the Soul

The “Gorgias” and “The Brothers Karamazov” portray the soul’s struggle to actualize its potential for order and stability. Tensions arise when one part of the soul takes over the others, as shown by the characters’ tribulations in both the novel and Plato’s dialogue. When Polus’s passion shapes his hostile words, conflict ensues. When Ivan’s reason dominates, he falls into despair. The struggle is internal and external. It happens within us and between us.Story continues below advertisement

In Socrates and Alyosha, we find two ordered souls. For Socrates, the soul finds unity only when reason takes over passion and the appetite. As he famously argued, “the unexamined life is not worth living.” Rational dialogue and self-examination help people understand that they should desire moderation, wisdom, and truth, and discard base pleasures, wealth, and power, just like him.

Dostoevsky might agree, but he might remind Socrates that reason alone can’t order the soul. It’s necessary, but insufficient. Unlike Socrates, Alyosha shows readers that the potential for goodness is revealed not in the triumph of reason, but in the crucible of suffering, faith, and redemptive love.

What arts and culture topics would you like us to cover? Please email ideas or feedback to features@epochtimes.nyc