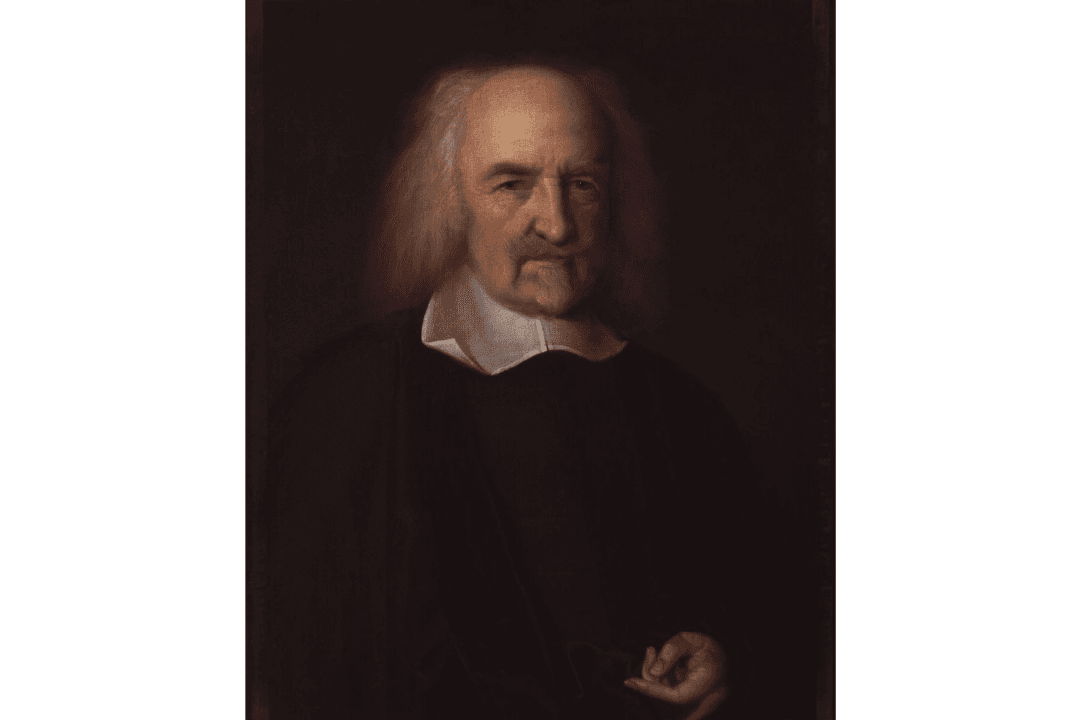

We owe the Founding Fathers’ notion of natural rights partly to Thomas Hobbes, whose “Leviathan” is one of the most radical and influential texts of the modern era.

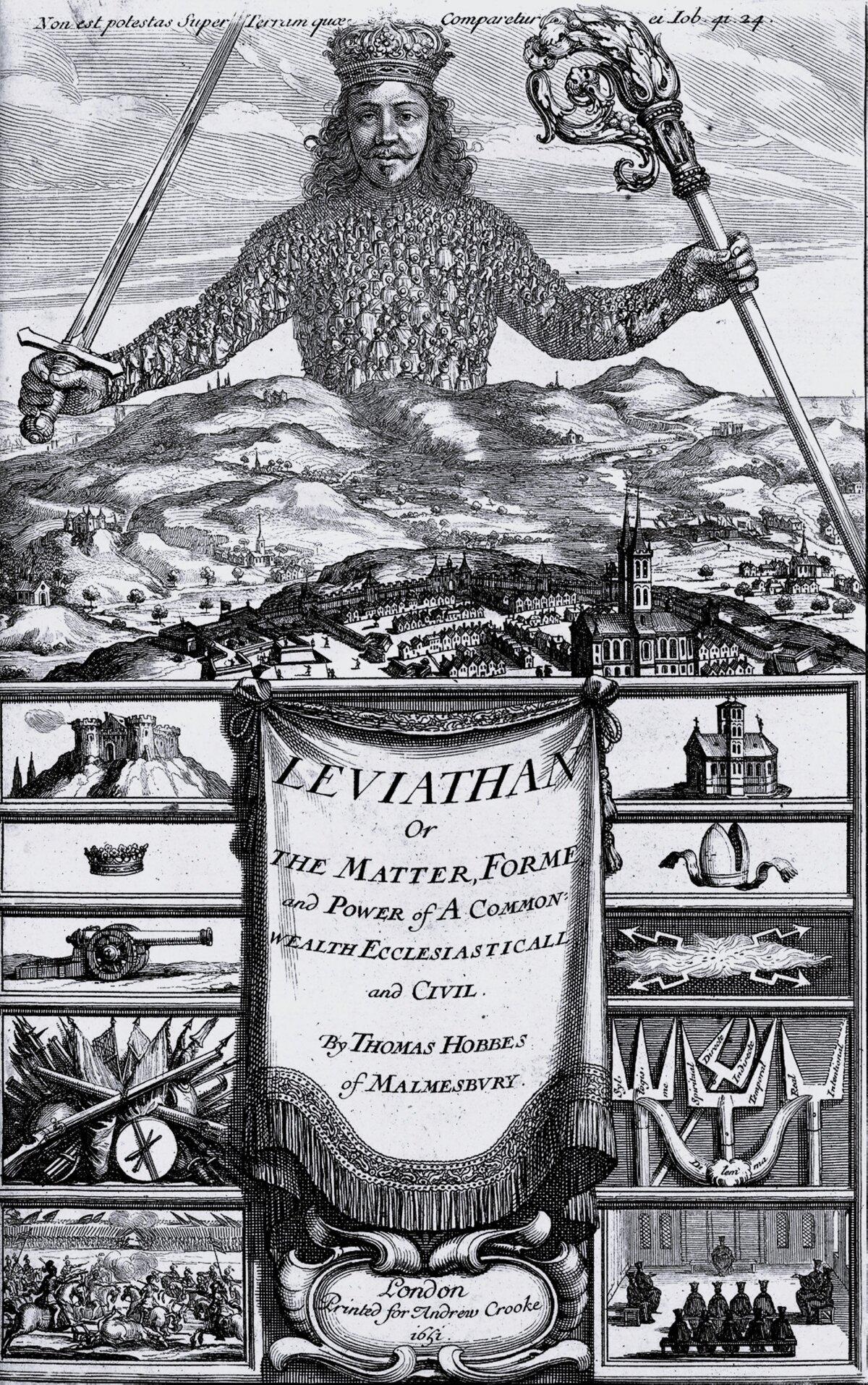

Frontispiece of "Leviathan" by Thomas Hobbes; engraving by Abraham Bosse. 1970gemini/CC0