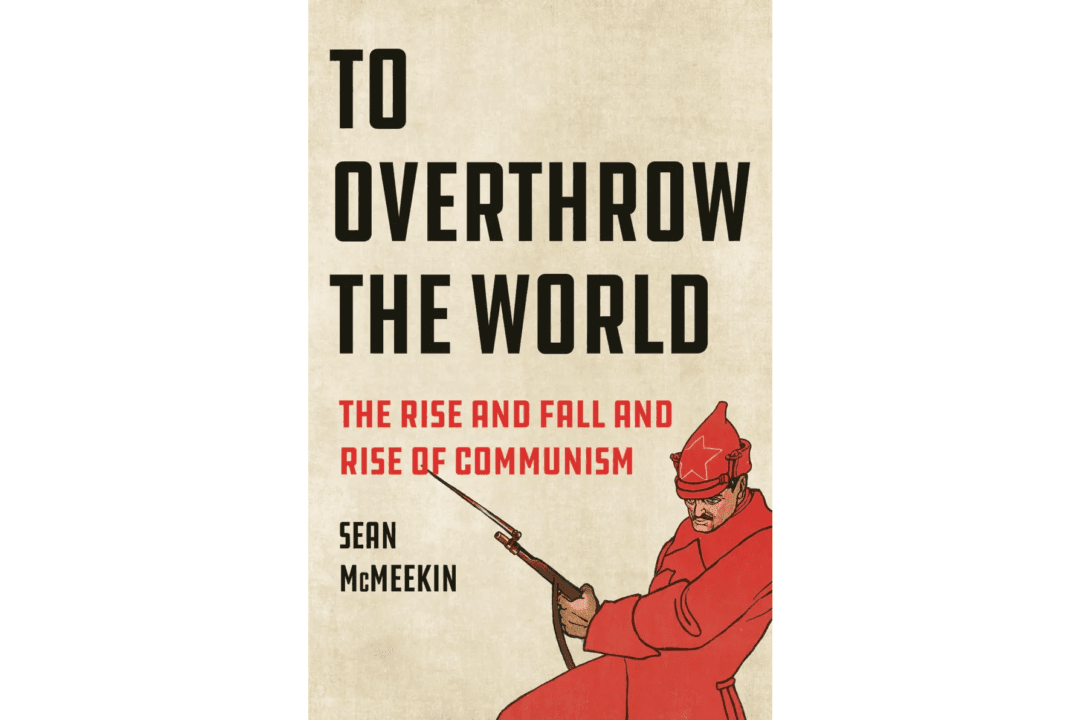

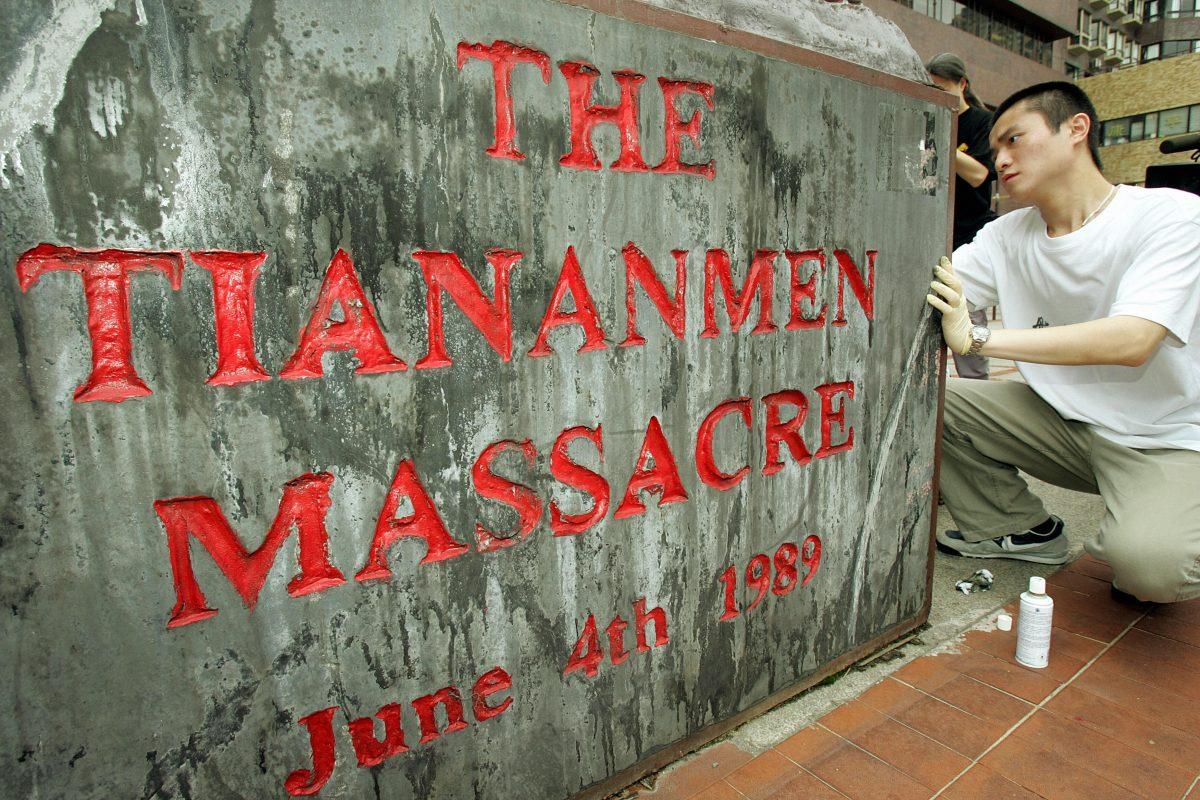

Part 1 of this two-part book recommendation shows how Sean McMeekin’s book “To Overthrow the World: The Rise and Fall and Rise of Communism” portrays the birth and growth of communism in the 19th and 20th centuries. In Part 2, McMeekin acknowledges that the fall of the Berlin Wall, the rending of the Iron Curtain, the collapse of the USSR, and an unprecedented uprising against the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in Tiananmen Square, all resembled the death throes of communism in the late 20th century.

A Hong Kong University student cleans a plaque below the "The Pillar of Shame," a monument constructed to honor the dead and shame the Chinese government that refused to apologize for the Tiananmen Square massacre, which killed students on June 4, 1989, in Beijing's Tiananmen Square. Mike Clarke/AFP/Getty Images