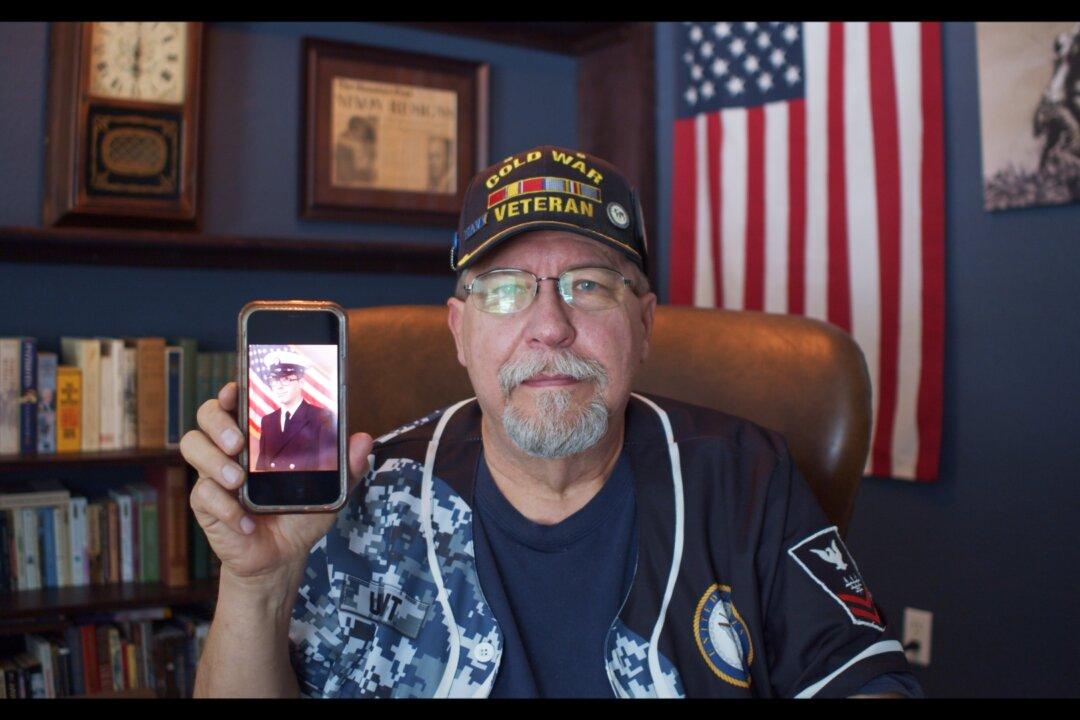

When Geoff Ugent was discharged from the U.S. Navy, he had to wait 27 years to talk about anything he did for the branch of the military. His former job title, ocean systems technician (OT), sounds more like he worked in oceanography or marine engineering than in one of the most select groups in naval intelligence.

“We were very rare,” Ugent said. “Most people in the military didn’t know what we were.”