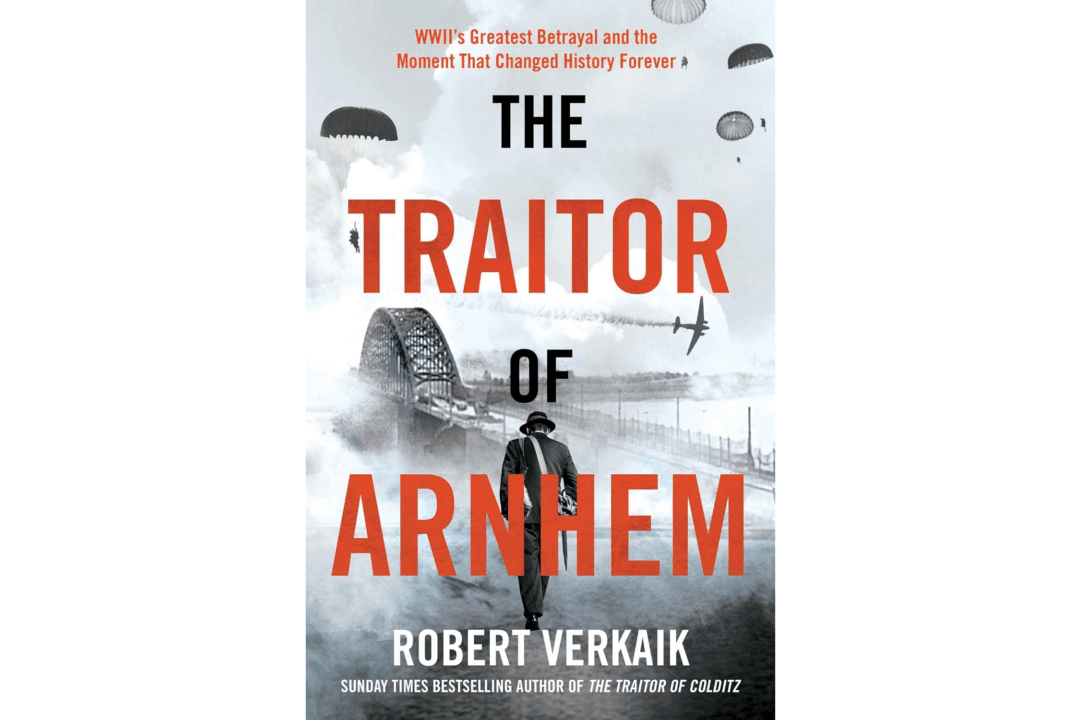

An ancient adage suggests that all warfare is based on deception. Robert Verkaik’s new work, “The Traitor of Arnhem: The Untold Story of WWII’s Greatest Betrayal and the Moment that Changed History Forever,” demonstrates just how true that statement is.

Verkaik’s book is broken into three sections that dive into the sordid details of espionage during World War II. His true tale of intrigue and betrayal follows the numerous paths of British, American, Russian, German, and Dutch spies that lead, ultimately, to one man.