Strategy of Claim Lower Now, Higher Benefit Later

The higher-benefit spouse defers but takes a spousal benefit from the account of the lower-benefit spouse while that lower-benefit spouse starts reduced payment from his or her own account at age 62. This is two draws from one account. (How long will Congress make this available?) The higher benefit spouse, upon reaching age 70 (maximized benefit), switches from the spousal benefit to his or her own enlarged account.

Effective in 2016, one popular strategy—not to be confused with the foregoing—no longer works. Previously, for a couple, the retiree with the highest payout could use the “File and Suspend” application option.

In that strategy, a worker filed on time, then immediately suspended receipt of payments. The spouse with the lower payout filed as what was called “restricted.” This enabled the “spousal benefit” (a special benefit intended to be for spouses who did not ordinarily qualify).

While taking the small spousal benefit that continued to grow at 8% annually, the other two primary Social Security payments were deferred, inflating at about 8% annually because neither was taken at all yet. The benefit taken was the smaller spousal benefit, while both primary benefits increased due to age step-ups. This was essentially a small but meaningful pre-benefit that was never intended to be for someone who had his or her own normal qualification for full benefits. But now, the spousal benefit suspends when the worker’s does, and there is no growth in spousal benefit. There is an exception for widows, and this can be used for widows who plan to remarry. One can fill out the forms for this strategy, but now that would result in no inflation at all for deferring and one would discover this after it was too late to change the original selection!

Another, simpler strategy is to take both benefits as early as they can be taken (even at the discounted rate for taking them slightly early) on the rationale that one might die unexpectedly, so you might as well get both as long as you can (remember, surviving spouses only get the larger of the two benefits, not both).

There are so many rules and resulting permutations of options and results that, like income tax planning and filing, sophisticated software is now absolutely necessary for maximizing benefit strategy. Further, these rules change so much—they constitute a political football—that you should avoid making any decision about your options based upon this or any book or seminar. Such references and annotations get dangerously out of date.

Here’s the secret: Do not figure this out yourself and then pick a strategy for filing. Filing strategies require software for maximization; even then you will be betting on the timing and order of your and your spouse’s mortality. These programs are best run by financial planners or Social Security specialists.

The good news is that if you use a professional for this analysis and counsel, you transfer the risk of making an uniformed decision to the professional (i.e., if there was negligence or an omission, that professional’s Errors & Omissions policy will enable recovery for a valid claim). Some insurers provide this without charge if you are willing to consider their investments or annuities. “Free” does not relieve the professional from the duty of competent analysis and counsel.

Case Study

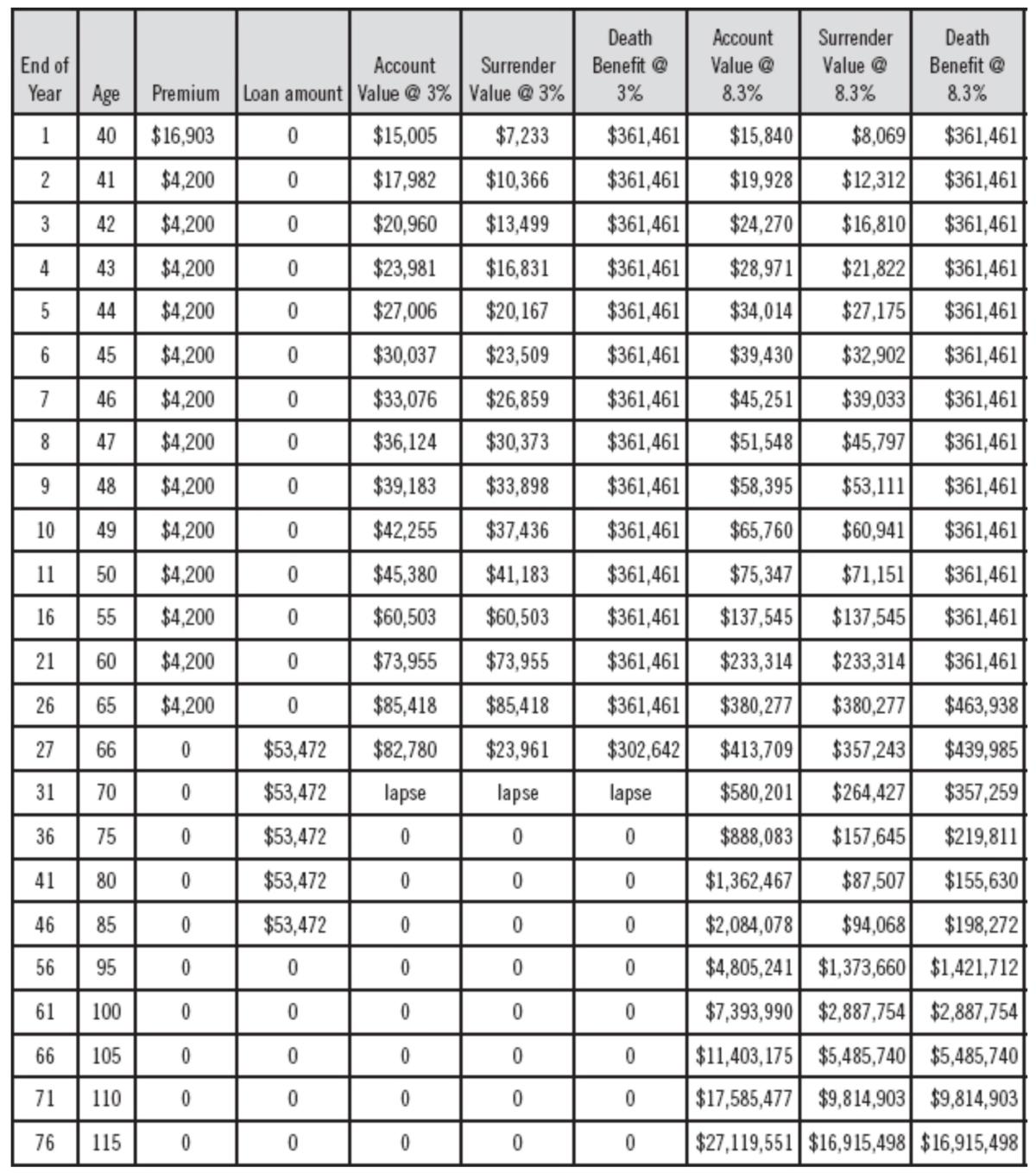

Indexed universal life insurance acting like a Roth account. Both provide tax-free income, but the policy also serves as a backup LTC policy.

Can’t put enough into a Roth? Need life insurance with LTC dual-purpose coverage and want the policy to also act like a Roth? As long as you recall that such a three-in-one policy can’t use a given dollar you take out for more than one purpose at a time, then consider this illustration of an actually issued policy and its details.

Summary of Indexed Universal Life policy from illustration ledger