Those growing up in the 1950s and 1960s knew about the Space Race. The United States and the Soviet Union were contending for mastery in the High Frontier. It looked like the Soviets were winning: first satellite in orbit, first animal in orbit, first man in orbit, first woman in orbit. The United States was hopelessly behind.

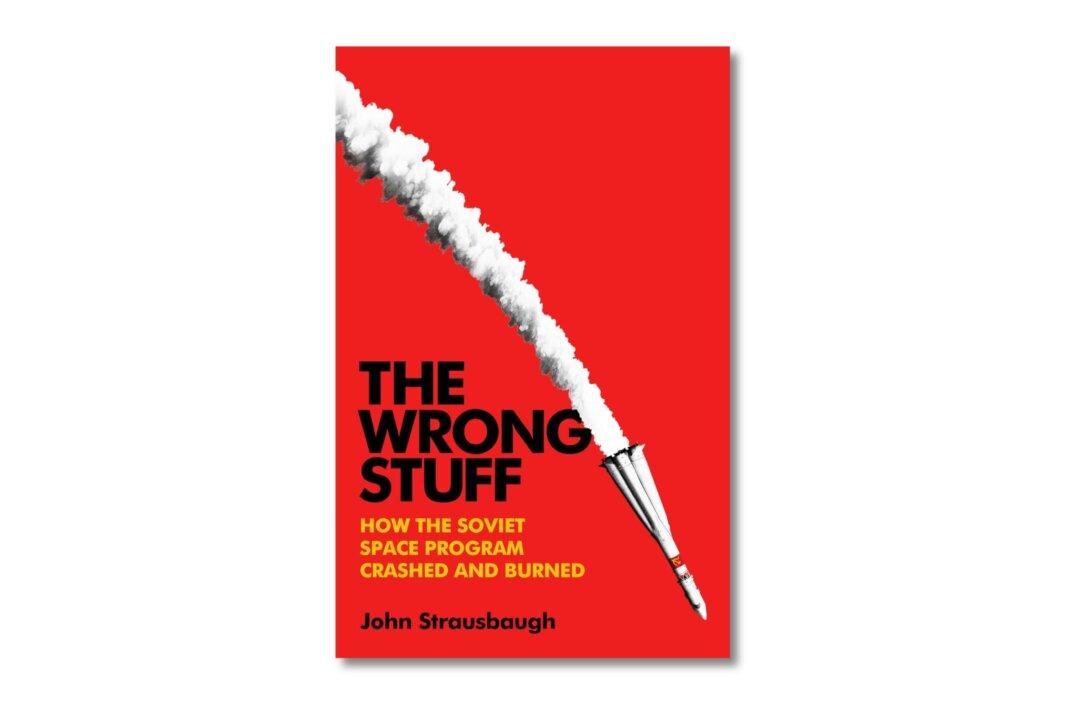

“The Wrong Stuff: How the Soviet Space Program Crashed and Burned,” by John Strausbaugh, reveals the reality. The Soviet Space program was a kludgy mess. Its only goal through 1969 was one-upping the United States, doing what the United States planned next in space before Americans could get to it. It existed to troll the United States.