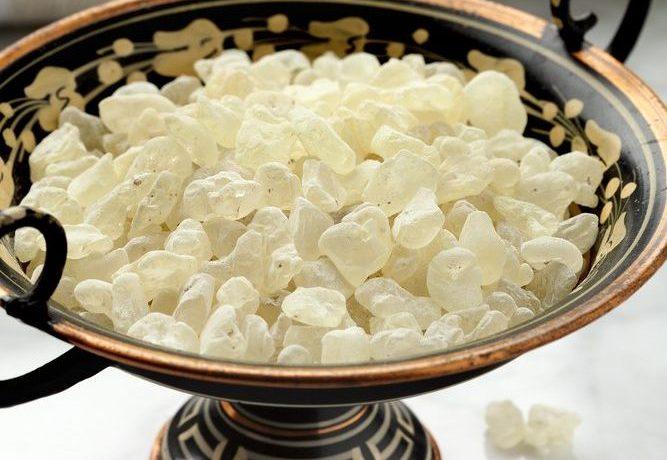

Mastiha, the fragrant, creamy white resin of the mastic tree, grows in only one place in the world: the island of Chios, Greece.

I had my first encounter with the mastic tree was when I was give years old. I was living on the island of Psara, Greece, about 14 miles northwest of Chios. My cousin Theodora wanted to play “doctors,” and I was so excited that while running up the steps made of uneven rocks, I fell and broke my arm. I had to go to Chios with my grandmother to have my arm set in plaster, because this could not be done on Psara.