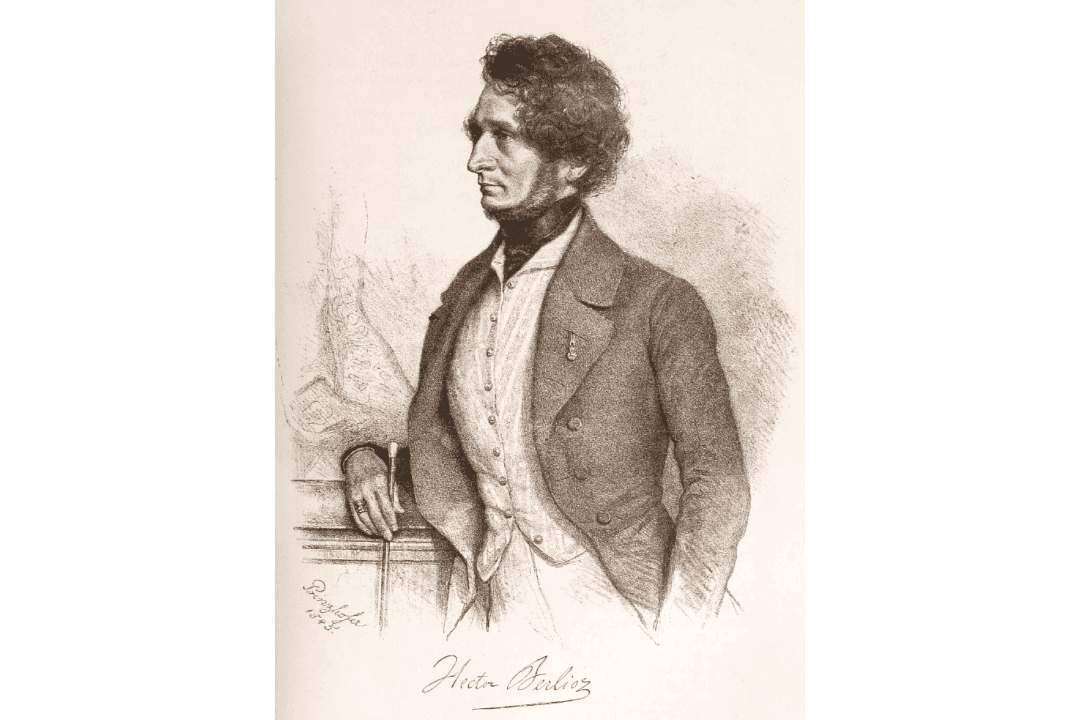

Hector Berlioz had an incurably sentimental personality. Moody and preoccupied with unrequited love, he fit the stereotype of the romantic artist perfectly. One of the women he longed for even inspired his greatest composition, the “Symphonie Fantastique.”

First Love

Berlioz fell in love for the first time when, at age 12, he became infatuated with a neighbor in pink shoes, Estelle Duboeuf. A young women of 18, she naturally turned him away and went off to marry someone else. Berlioz found himself unable to forget her, however. He turned to music for consolation, learning the flute and studying harmony.Berlioz’s early works were inspired by Estelle and he wrote two quintets, which he later burned. “Nearly all my melodies were in the minor mode,” he wrote of his melancholy style. “A black veil covered my thoughts.”