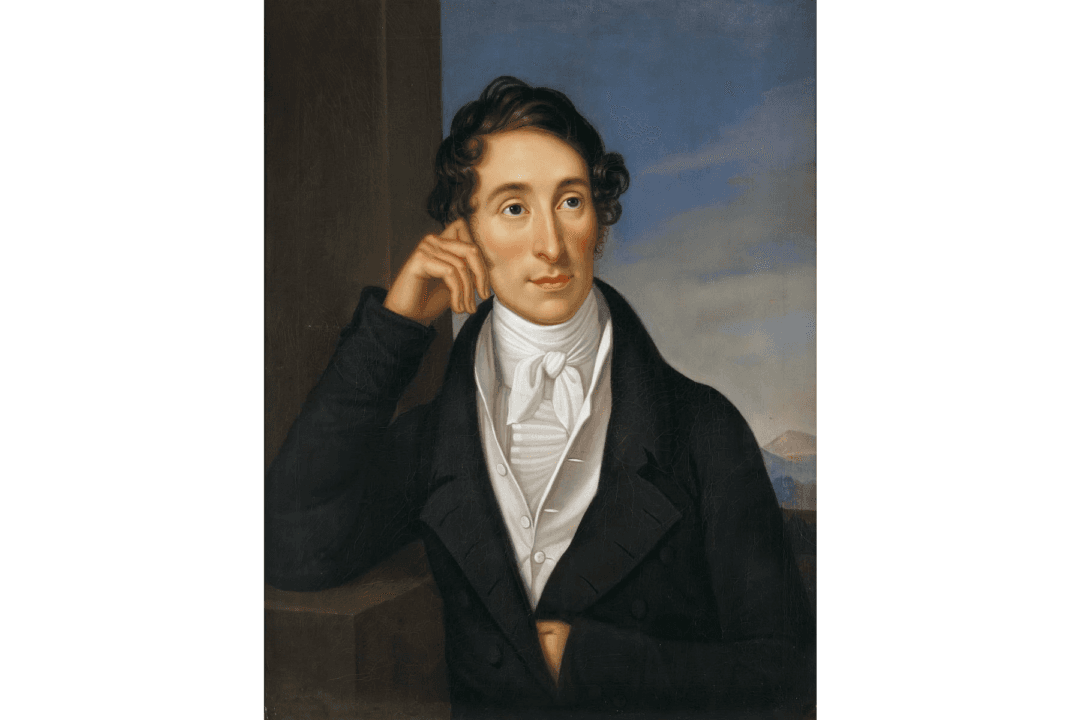

Carl Maria von Weber is considered the founder of German romantic opera. He was not the first to write an opera in that language (Mozart preceded him), but he drew on uniquely German cultural themes as no one before him had. Though he died young, he left an indelible impact on those who came after him, particularly Richard Wagner.

Early Life and Success

Weber was born in 1786 in the town of Eutin, Germany, 20 miles north of Lübeck. His father was a musician and traveling actor, and young Carl first learned to play an instrument while traveling with the caravan. When his uncle, Fridolin, attempted to give Carl, age 3, a music lesson, Fridolin tore the bow from the boy’s little hands and said, “Whatever else may be made of you, you’ll never be a musician!”Despite this, Weber soon showed a genius for music. He grew up to become accomplished in several areas, not only as a composer but as a conductor.