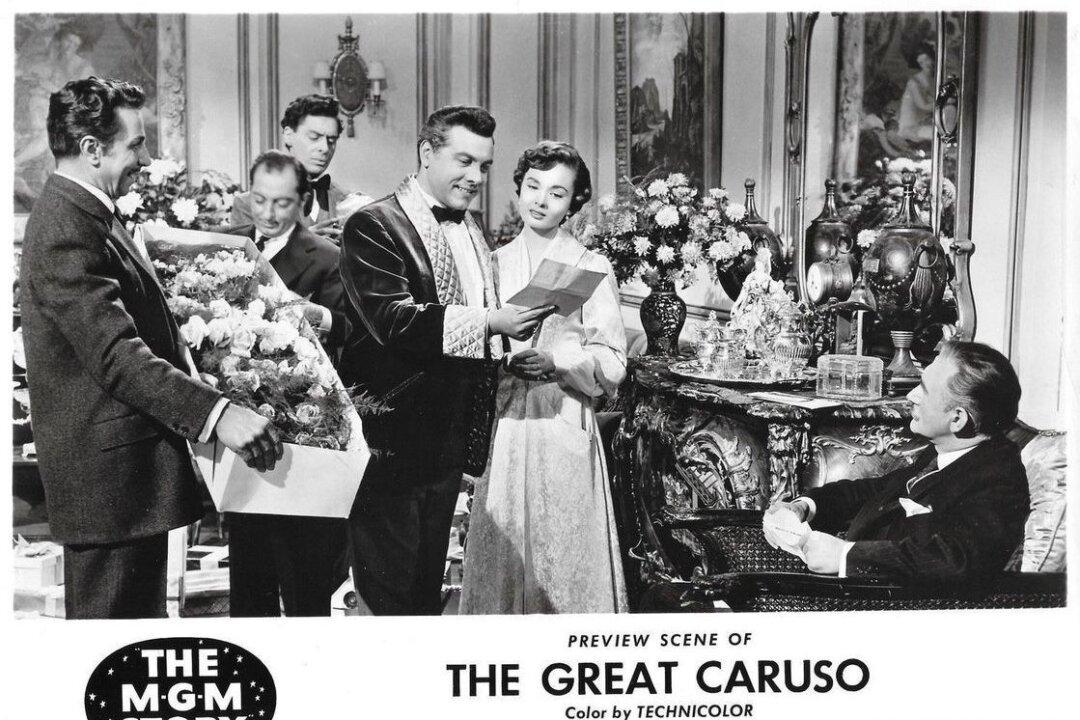

NR | 1h 49min | Drama | 1951

Director Richard Thorpe’s fictionalized story of Italian operatic tenor Enrico Caruso draws on a sympathetic biography by Caruso’s wife, Dorothy. Charismatic tenor-actor Mario Lanza brings the power, presence, and passion of Caruso’s legendary voice to life on screen.