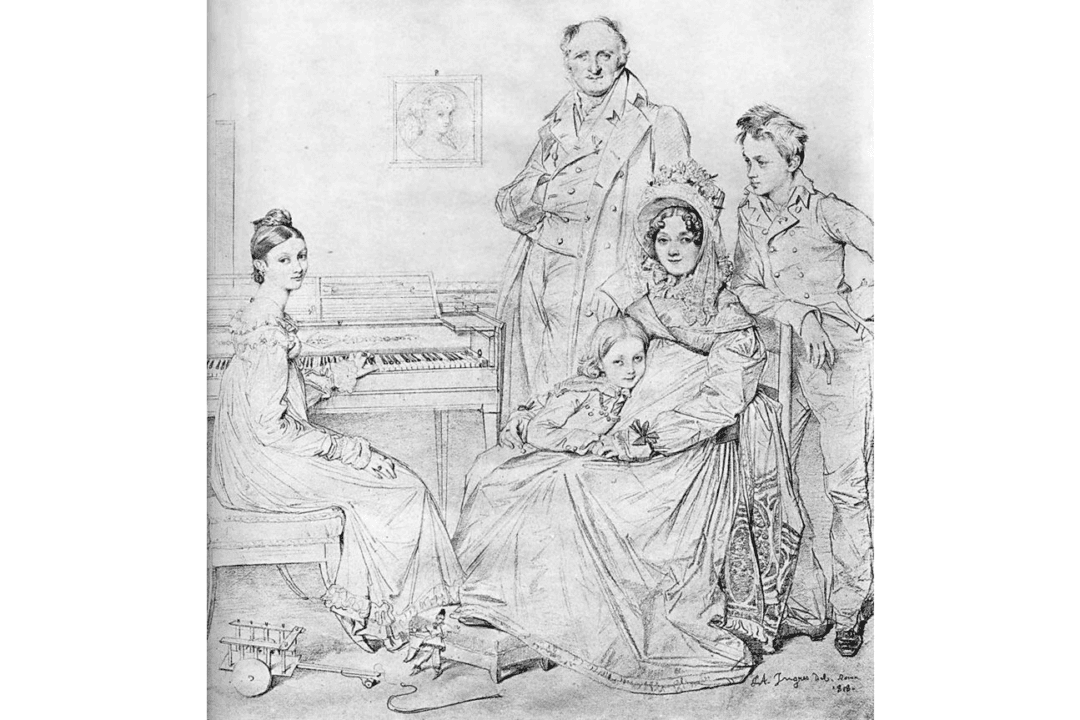

Families who lived in France during the Napoleonic era made strong and resilient homes in their country. Their homes were built not of bricks and mortar, but of caring and love. This is evident in the skillful portrait sketches of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867), who presented the prosperous and loving middle-class families of this time.

Parent and Child

In many of his drawings, Ingres showed the strong bond of parent and child through their expressions. When he prepared to sketch, he carefully observed the face of each sitter. He once said: “To really succeed in a portrait, first of all one has to be imbued with the face one wants to paint, to reflect on it for a long time, attentively, from all sides, and even to devote the first sitting to this.”In the sketch of Charles Hayard and his daughter Marguerite, we see the protective embrace that a father gives his child, and the little girl rewards that care with a child’s trust as she holds her father close to her. From the top hat on the chair, purposely placed in the composition, we assume Hayard has just returned or is just about to leave, as he still wears his topcoat. His daughter greets him or, possibly, wishes him goodbye. The pose is immediate and casual.