In the 1970s and early 1980s the stock brokerage firm E.F. Hutton aired a series of television commercials with the slogan, “When E.F. Hutton talks, people listen.” Today, when renowned military historian Victor Davis Hanson warns the country to learn from past lessons of barbarism and the obliteration of entire civilizations, people notice.

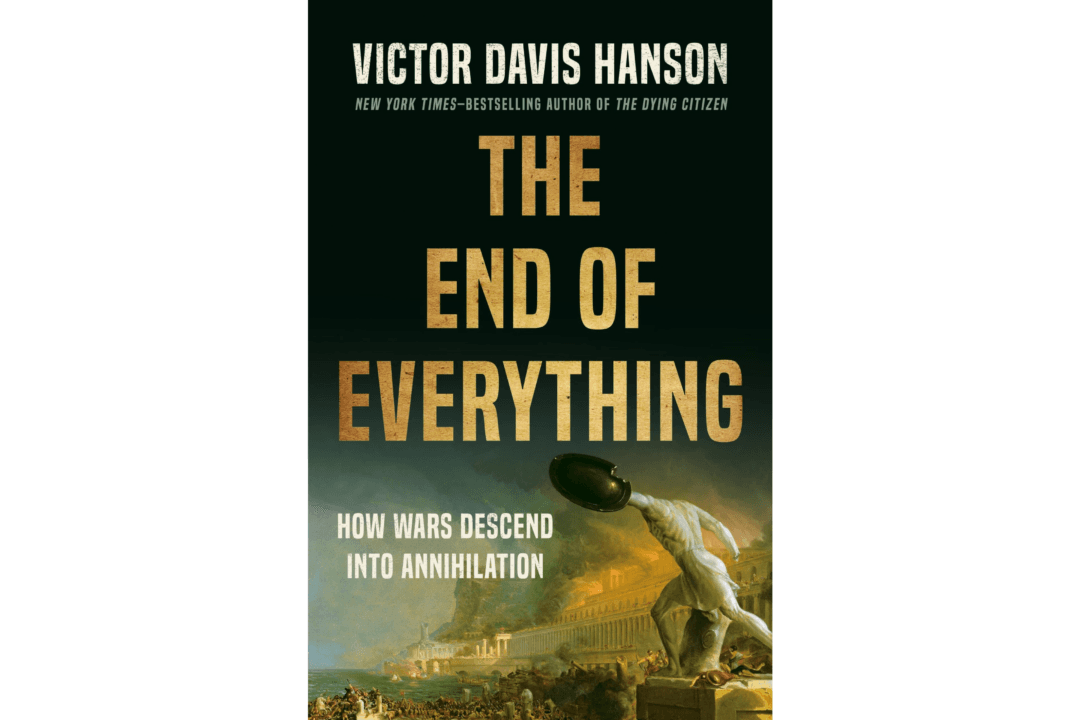

Mr. Hanson is a senior fellow in American military history at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University and a professor emeritus of classics at California State University, Fresno. He is also a best-selling author of two dozen books. His latest book “The End of Everything: How Wars Descend into Annihilation” is a sobering recap of how and why four formerly thriving civilizations literally ceased to exist.