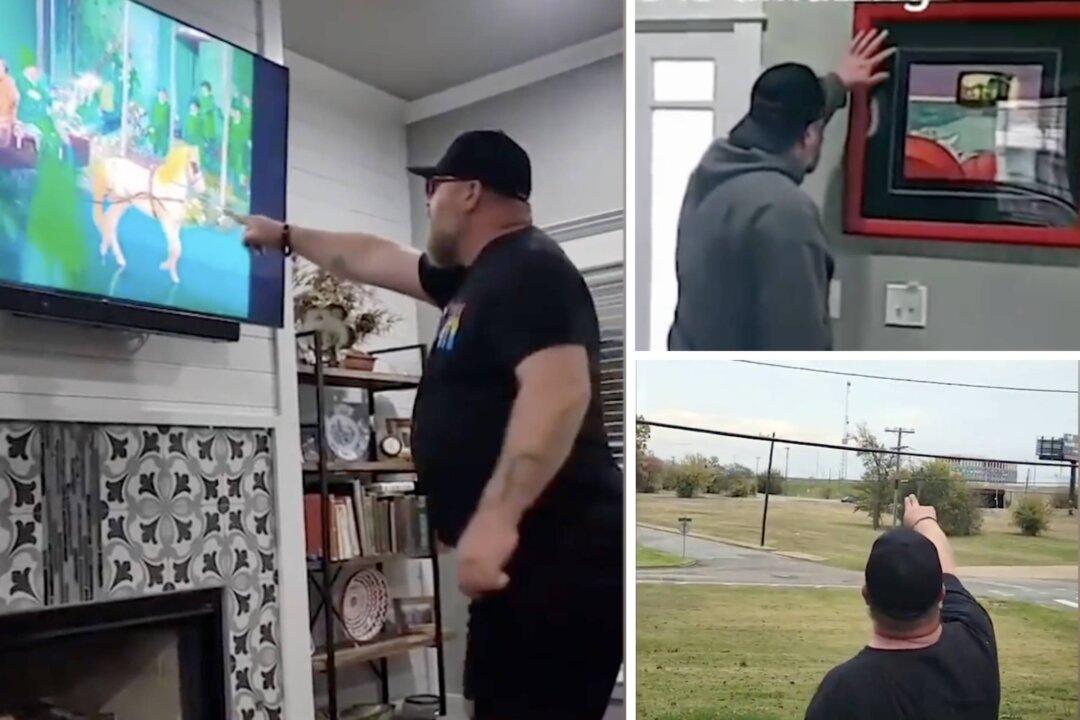

How an American pilot dropped Hershey’s on East Germany to give them a taste of freedom

The Berlin Airlift remains one of the greatest Allied achievements of the Cold War, a moment where bombers were repurposed to drop large quantities of food and coal to a starving, freezing civilian population. But decades later, it wasn’t the essentials the bombers brought that Berliners remembered best—it was the candy.For the young people of Berlin, whose childhood had been taken away from them by war, Gail Halvorsen, the Air Force bomber captain behind the drops of sweets whom they knew as “Uncle Wiggly Wings” and the “Chocolate Pilot,” came to be the symbol of hope for freedom and a better future.