G | 1h 58m | Drama | 1979

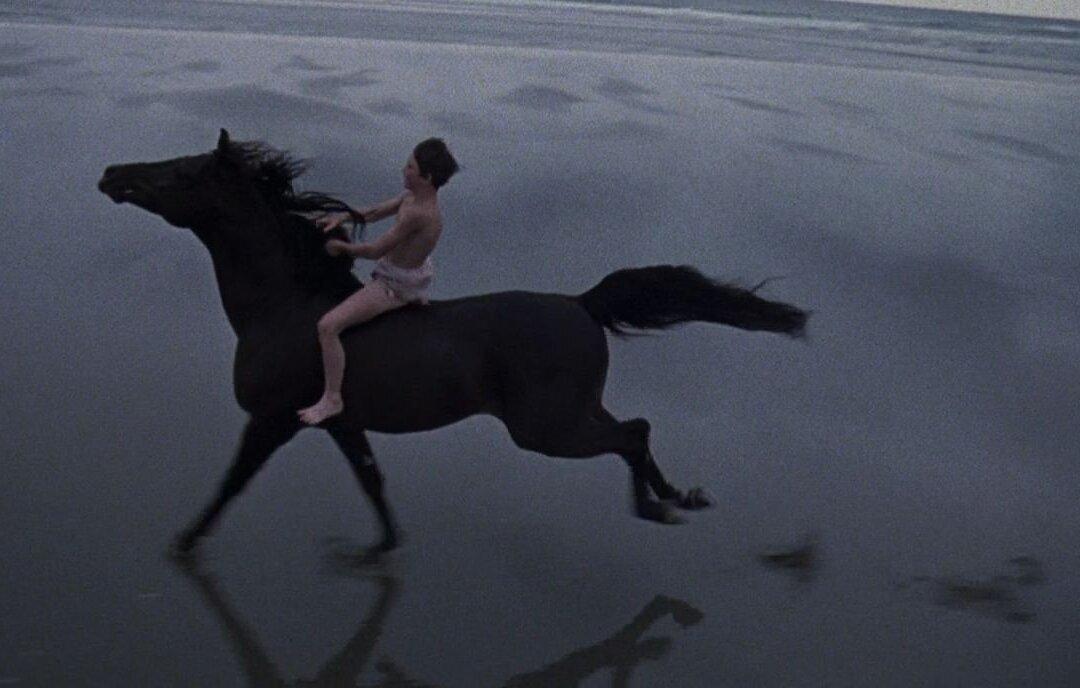

This film, about the mystical bond between a boy and his horse, draws on Walter Farley’s novel set in the 1940s.

G | 1h 58m | Drama | 1979

This film, about the mystical bond between a boy and his horse, draws on Walter Farley’s novel set in the 1940s.