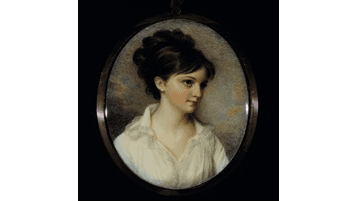

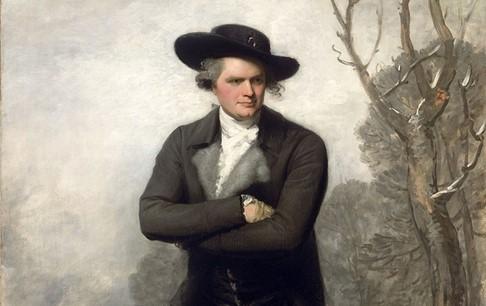

Parents often keep a photo of their children in a wallet or purse. Although worn and wrinkled, the photo keeps their children close to them as they go about their daily life. Families in the 18th and 19th centuries had the same wish, and so miniature paintings grew in popularity among prosperous early Americans.

Usually no more than two inches, a miniature was made to be held in the hands of a single viewer to create a sense of intimacy with a loved one when physical proximity was not possible, either for engaged couples or loved ones separated by war. Placed into small frames, the miniatures could be pinned inside a jacket or placed in a pocket for easy access to look at throughout the day.