Have you ever been thrilled by the power and majesty of nature? Have you ever had your mind opened to new vistas by encountering a great work of art? Have you ever lost a friend or a loved one? If you’ve had any of these occurrences in your life, then the poems in this article, which deal with such experiences, will speak to you, inspire you, and maybe even comfort you.

‘Pied Beauty’ by Gerard Manley Hopkins

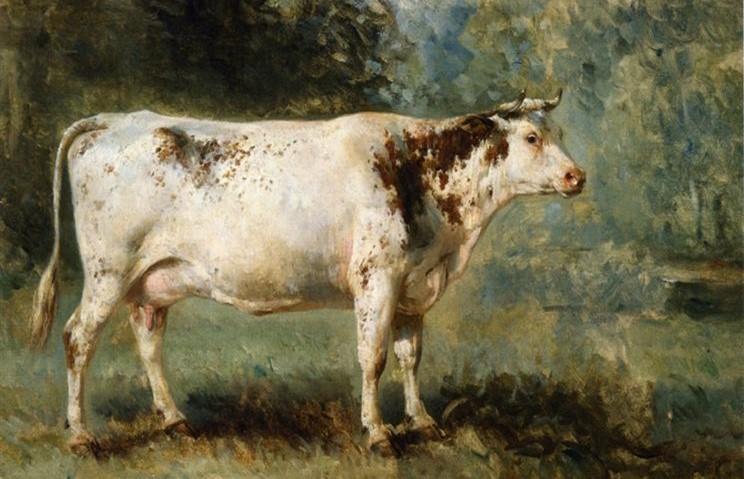

Glory be to God for dappled things – For skies of couple-colour as a brinded cow; For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim; Fresh-firecoal chestnut-falls; finches’ wings; Landscape plotted and pieced – fold, fallow, and plough; And áll trádes, their gear and tackle and trim. All things counter, original, spare, strange; Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?) With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim; He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change: Praise him.

Gerard Manley Hopkins, a 19th century English priest, possessed the gift of true sight. That is, he was able to truly see things as they are, in all their glory, strangeness, rarity, and beauty. He found ecstasies of delight in the smallest details of the countryside and the city, human life and the natural world, and in things that many of us dismiss or do not notice.