What could a 700-year-old medieval poem possibly have to say to us about the nature of suffering that would be relevant in the year 2025? Quite a lot, as it turns out.

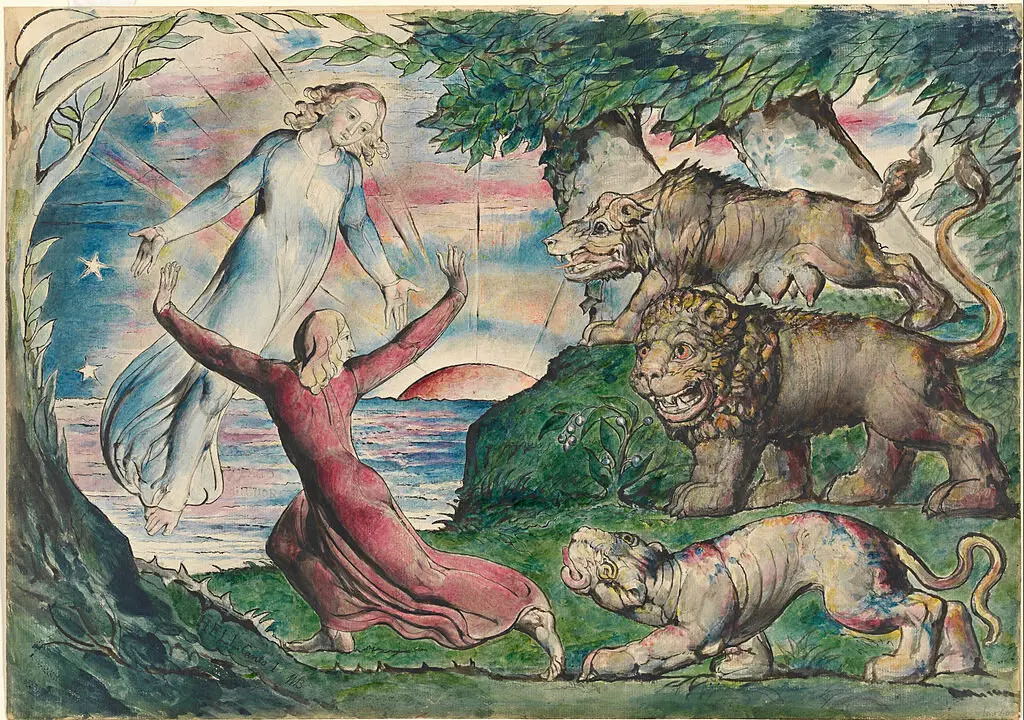

“The Divine Comedy,” written by Dante Alighieri in the early 14th century, tells of the pilgrim’s spiritual journey through the realms of the afterlife: Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven. Dante’s towering poem plunges to the harrowing depths of Hell and surges to the luminous pinnacles of Heaven, encompassing the full range of human emotion and experience, encapsulating the entirety of the human and divine drama.