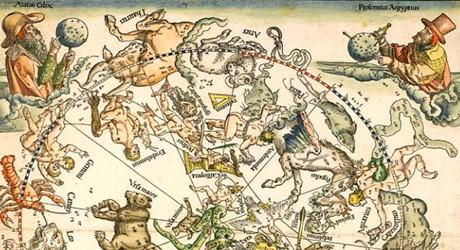

The ancient Greeks considered the stars as celestial beings who made their home in the night sky: a great bear, a fish, a winged horse, Perseus holding the head of the Gorgon, and even Hercules shined above the earth every night. Artists and scholars in the Renaissance studied what the ancients had discovered about the constellations and made it their own.

The 15th-century city of Nuremberg, Germany, was alive with discoveries in the arts and sciences, including astronomy and astrology. Schools of the natural sciences and technology, outstanding artists’ workshops, commercial firms, and publishing houses found ways in which they could work together to expand knowledge and technical skills and produce works of outstanding beauty.