SAN FRANCISCO—This October, the city’s concert-goers could choose between such exotic locations as Poland and Greece with a rare performance of symphonic music by Szymanowski, and Mozart’s first major opera Idomeneo (The King of Crete). Both events featured world-renowned guest stars, most notably pianist Emanuel Ax in concert with the San Francisco Symphony and tenor Kurt Streit in the title role of the San Francisco Opera’s latest production.

A Sacrifice to Neptune

Known especially for his interpretation of Mozart, American tenor Kurt Streit made his fifth appearance with the San Francisco Opera, this time as the heroic ruler of Crete—a role that he has sung with major opera companies worldwide.

Based on a libretto by Giambattista Varesco, the opera portrays the powerful king Idomeneo having to sacrifice his own beloved son Idamante to prove his devotion to Neptune, the god of the sea, and to redeem his people from terrible consequences. It is a familiar fable with religious overtones reminiscent of the story of Abraham and Isaac or the Passion of Christ.

The opera’s subplot is a love triangle with Idamante falling in love with Ilia thereby rousing the jealousy of Elettra, who has her own ambitions of becoming the next queen of Crete. To further complicate matters, Ilia is a Trojan while Idamante is a Greek—not a good combination given Troy’s recent humiliating defeat and the long-standing blood feud between the two nations.

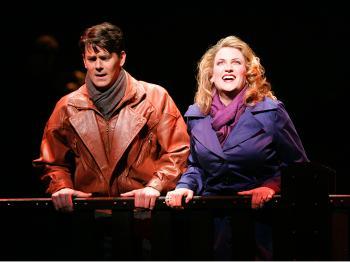

British mezzo-soprano Alice Coote appeared as Idamante, the son of Idomeneo, and sang with amazing clarity and control, particularly in light of the pre-performance announcement that she was under the weather. Coote reached her highest point in the aria “No, la morte” in the third act, where Idamante heroically offers to die so that his father’s life may be spared.

The reason for choosing a female to play the male role of Idamante deserves a brief mention. Europeans had discovered that boys castrated before puberty would often develop a powerful soprano voice well-suited for reaching large audiences. This gave rise to a special group of male sopranos especially trained from childhood for the operatic stage. Consequently, many major composers of opera—including Mozart—wrote parts for male characters in the soprano range, which are now performed by female singers.

Austrian soprano Genia Kühmeier gave an absolutely stunning performance as the object of Idamante’s affection, Ilia. Her aria “Se il padre perdei” in Act II was a touching moment of the opera, when Ilia not only forgives Idomeneo for having killed her father during the Trojan War but also embraces the King of Crete as her adopted father. Kühmeier seems to have devoted much of her career to the music of Mozart, clearly with astounding results.

The gifted Georgian soprano Iano Tamar appeared as Ilia’s conniving rival, Elettra, while American tenor Alek Shrader beautifully sang the part of Arbace, Idomeneo’s limping confidant and adviser.

The sets were designed by John Conklin and featured assorted classical marble surroundings, which split apart to reveal brightly painted panoramic backdrops of the Mediterranean. One of the most remarkable sets was in the opening scene, with vivid blue accents in the décor and in Ilia’s costume against a white backdrop—perhaps a reference to the Greek flag.

The opera was directed by San Francisco Opera’s long-time collaborator, John Copley. Ian Robertson led the San Francisco Opera Chorus as the people of Crete, and music director Donald Runnicles conducted the orchestra in yet another flawless performance.

Lucky for all but Elettra, the heretofore vengeful Neptune has a sudden attack of clemency at the end of the opera and forgoes the sacrifice owed him, under the condition that Idomeneo take an early retirement as the king of Crete and allow Ilia and Idamante to marry and become his successors to the throne.

Symphony Guests Ax and Oundjian Take Center Stage

Distinguished pianist Emanuel Ax joined conductor Peter Oundjian of the Toronto Symphony in a special concert of the San Francisco Symphony on Oct. 11. The program opened with Mozart’s Overture to the opera The Magic Flute and featured Emanuel Ax as the soloist in Karol Szymanowski’s Symphonie concertante and Burleske by Richard Strauss. The evening concluded with Tchaikovsky’s rarely performed Francesca da Rimini.

Although Mozart’s opera overtures are commonly included in symphonic programs, this one had a special ingredient: Peter Oundjian. We often think of Mozart as not only a precocious genius of his time but also as a sort of musical prophet whose works foretold—or rather shaped—the evolutionary course of the art in Europe and in the western world. Consequently, Mozart’s music is often approached with a certain cautious reverence as, say, ancient scripture or a holy relic.

In Oundjian’s interpretation, however, we heard neither a faded Mozart covered in the dust of the centuries nor a scholarly approximation of how the music would have been played in the composer’s time. What we heard was a clear, lucid voice speaking in a fundamentally human language, as compelling today as it must have been in 1791. Oundjian’s Mozart was fresh, energetic, clean, bright, and decidedly devoid of cobwebs.

Where the words “Poland” and “music” appear in close proximity, the name “Chopin” is usually somewhere in between. Since the middle of the 19th century, only a few musically gifted sons of Poland have managed to pierce through the shadow of the legendary giant of the piano. Among these were Ignacy Paderewski and Arthur Rubinstein, both blessed with successful careers; each hailed as a musical heir to Frédéric Chopin. Pianist and composer Karol Szymanowski was on the list that got filed away—at least until now.

The Symphonie concertante by Szymanowski calls for an exceptionally large orchestra, making even the massive stage at Davies Symphony Hall look overcrowded. With this highly skilled army of musicians, the score’s centerpiece was a demanding part for the piano, which Emanuel Ax tamed with effortless elegance.

The piece offered a journey in three movements across an eclectic soundscape, spanning in style from Mendelssohn to Prokofiev by way of Wagner with a brief detour through Ravel. Beneath its strikingly rich orchestration, the music had an undeniably pessimistic undercurrent with percussive rhythmic motives suggesting war and conflict—perhaps a musical premonition of Poland’s tumultuous times ahead.

Emanuel Ax’s thoughtful performance of this obscure piece by little-known Szymanowski certainly breathed new life into both composer and composition. Having briefly lived in Poland as a child, Ax has not only the artistic, but perhaps also the cultural, credentials to re-introduce Szymanowski to the world.

A high point of the evening came with Burleske for piano and orchestra, composed by a youthful Richard Strauss near the peak of his musical prowess. While the title somewhat undermines the piece’s importance as a serious work of art, it is nonetheless an astonishing feat in orchestration even by modern standards.

Writing in sonata-allegro form, Strauss drew from an inexhaustible palette of symphonic color to bring into focus his graceful and heroic themes on the piano, which Emanuel Ax delivered with exceptional sensitivity. We also got a glimpse of the composer’s flair for the dramatic with a recurring melodic solo for the timpani.

Requiring Rachmaninoff-sized hands, this piece is accessible only to the finest of pianists, which also explains why the work is performed so infrequently. For the second time in a single evening, we discovered a precious musical gem thanks to Emanuel Ax and his intimate knowledge of the seldom-visited shelves in the Romantic section of the world’s proverbial piano library.

The last piece on the program was Tchaikovsky’s symphonic poem inspired by the character of Francesca da Rimini, who, according to Dante, is trapped in the second circle of hell for the mortal sin of lust. This was a particularly powerful piece, ranging in emotion from tenderness to terror with musical fragments reminiscent of Tchaikovsky’s better-known orchestral works, particularly his tragic ballet music.

The flames of hell were represented by a furiously rising and falling chromatic motif in a hypnotic and frightening pattern. This always followed a delicately orchestrated passage of sublime beauty, possibly a musical representation of earthly love. A connection may be drawn between this piece and the composer’s personal struggle in a world dominated by Victorian notions of propriety.

In an impressive finale, Peter Oundjian was mesmerizing as his baton traced around him a frenzied blur—not unlike a saintly halo—while he feverishly conducted his way through the depths of Tchaikovsky’s hell with sweeping, passionate strokes. The ensuing standing ovation was well-deserved.

Eman Isadiar teaches piano at the Peninsula Conservatory and writes about music in the San Francisco Bay Area.