Love Potion No. 9?

Donizetti is considered a relatively minor composer when compared to such giants of Italian opera as Rossini, Verdi, and Puccini, yet, surprisingly, he has left some 75 operas of which two have become immensely popular, namely Lucia di Lammermoor and L’elisir d’amore (The Elixir of Love). With its humorous plot and happy ending, it’s no wonder that the San Francisco Opera has chosen “Elixir” as this season’s family-friendly production, with several educational matinees aiming to introduce children to opera.

The most striking feature of the production was a kind of cultural “grafting,” infusing this very Italian opera with a very American feel. The centerpiece of the brightly-lit set was a pavilion structure or gazebo with prominent colonial elements, such as one might find on a public square in a small town in, say, Napa Valley circa 1915. A Model-T Ford ice cream truck parked to the side of the stage, and the stars and stripes adorning the pavilion’s eaves set the scene squarely in Anytown, USA. This highly original twist to Donizetti’s opera was conceived and designed by director James Robinson.

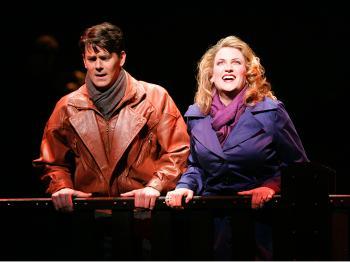

The opera is about a humble young man named Nemorino, who is infatuated with the sophisticated Adina. When the charming Sergeant Belcore visits the town to find new army recruits, Nemorino fears that Adina will marry the officer. So he drinks a red potion tasting very much like Chianti, which is sold to him by a traveling “doctor” named Dulcamara, who claims the concoction will make any man who drinks it irresistible to women.