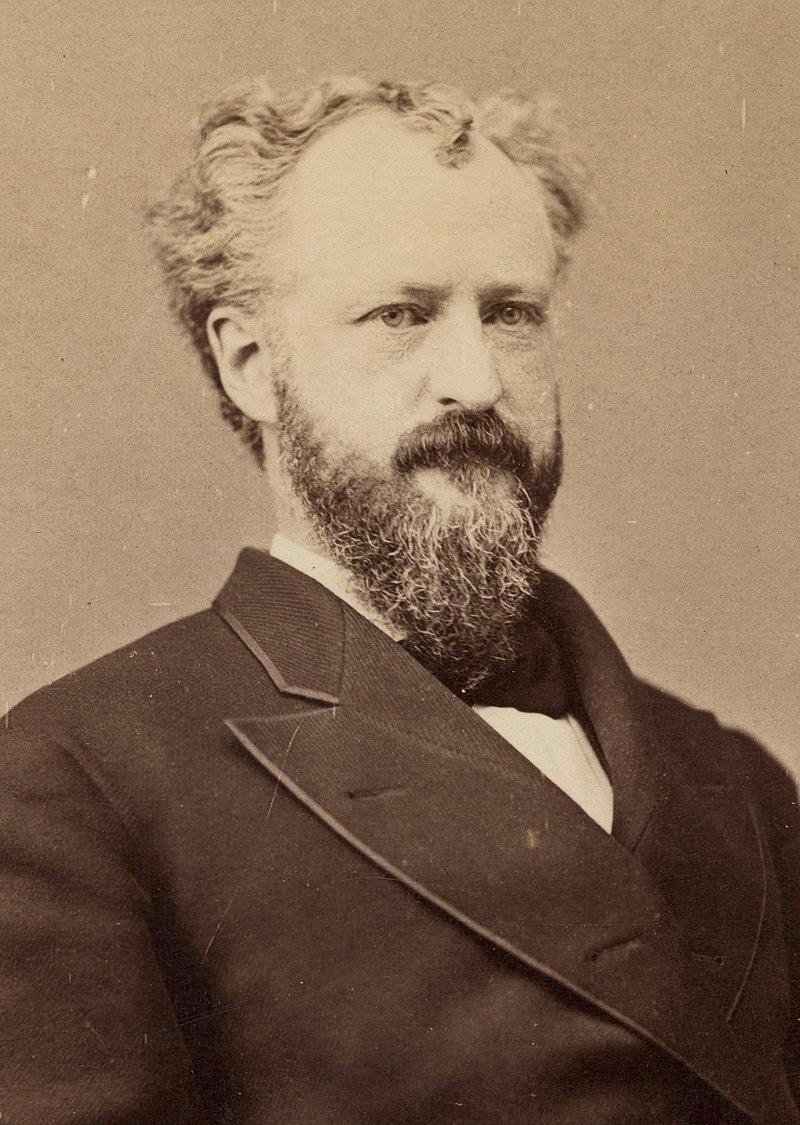

Charismatic and silver-tongued, Roscoe Conkling (1829–88) was also known for his fiery temper. He helped launch the Republican Party, a political successor to the Whig party, and worked his way as a force to be reckoned with in New York politics. The 19th-century politician may have made more political adversaries than friends, but his intelligence and fierceness helped end slavery and give rights to freed slaves. Although his stubbornness contributed to his success in politics, it ultimately led to his demise.

A portrait of Roscoe Conkling, circa 1876 from an 1868 negative, by John F. Jarvis. National Portrait Gallery. Public Domain