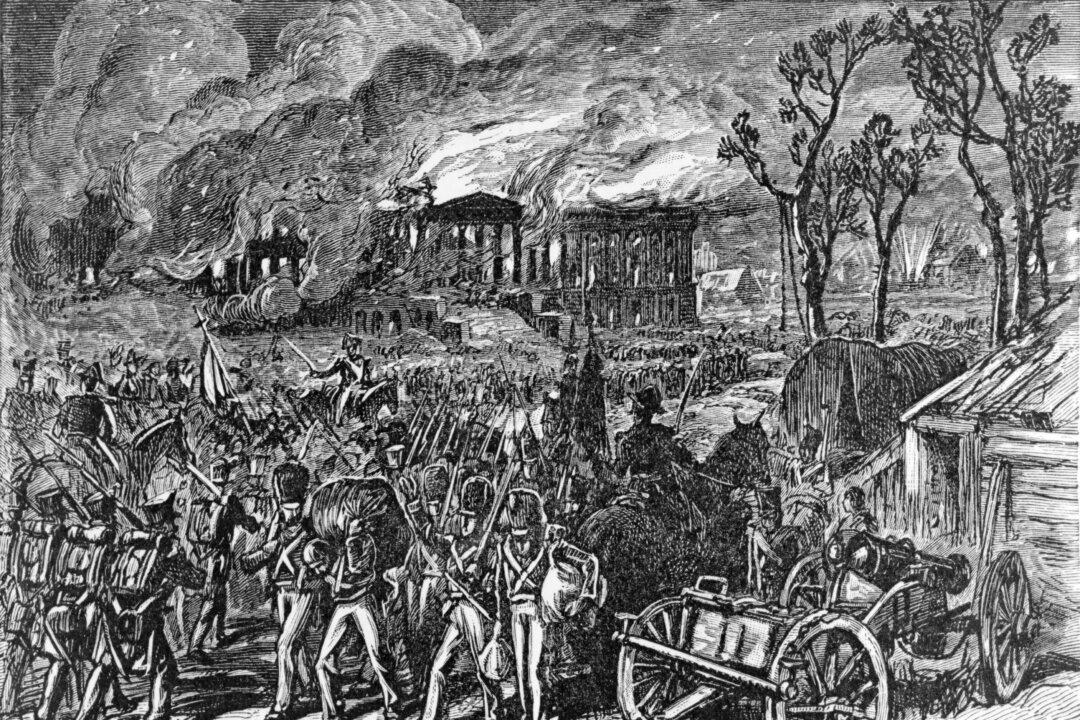

As the Executive Mansion, now known as the White House, and other buildings burned in Washington during the War of 1812, clouds darkened the sky. A vicious thunderstorm struck the region and turned into a tornado that wreaked further chaos. After the rain extinguished the flames, the weather events that occurred that day became known as the “storm that saved Washington.”

How the City Came to Burn

When the United States declared war on Britain in 1812, the British were spending most of their resources battling France in the Napoleonic Wars. But when France was defeated in the Battle of Paris in 1814, Britain sent many of their experienced soldiers to fight in America.After U.S. troops had set fire to the Canadian capital, York (present-day Toronto), during the Battle of York in 1813, Britain soon chose to attack Washington. Britain sent Maj. Gen. Robert Ross along with around 4,500 troops to Washington.