Sometimes you know in an instant that you are going to really like a place.

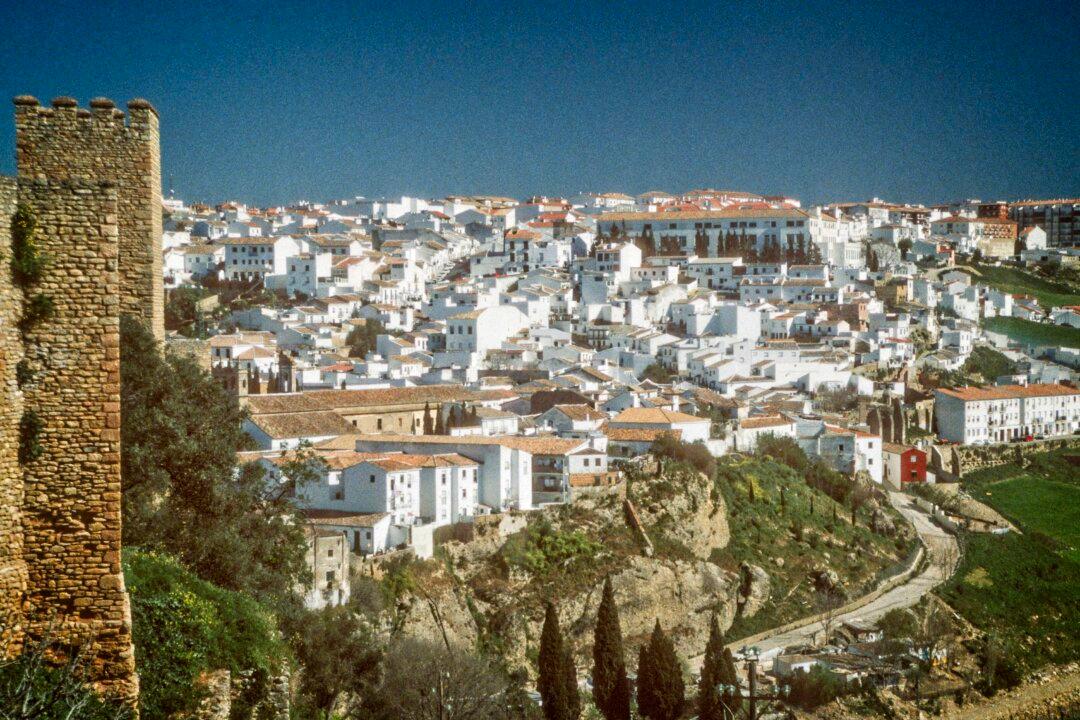

That’s how my wife and I feel as we gaze over the Andalusian plains up toward a towering plateau and for the first time feast our eyes upon the small Spanish town of Ronda.

Sometimes you know in an instant that you are going to really like a place.

That’s how my wife and I feel as we gaze over the Andalusian plains up toward a towering plateau and for the first time feast our eyes upon the small Spanish town of Ronda.