In “Radical Wolfe,” director Richard Dewey uses a Vanity Fair article, penned by writer Michael Lewis, about now-legendary American novelist and journalist Tom Wolfe (author of “Bonfire of the Vanities”) as a sculpture armature around which to build the narrative. Lewis wrote the source material that inspired the likes of “Moneyball,” “The Big Short,” and “The Blind Side,” and clearly sees Tom Wolfe as a hero and mentor.

‘Radical Wolfe’: American Literary Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing

“Radical Wolfe” reveals author Tom Wolfe to be an unflappable, powerfully principled, conservative-leaning, old school family man.

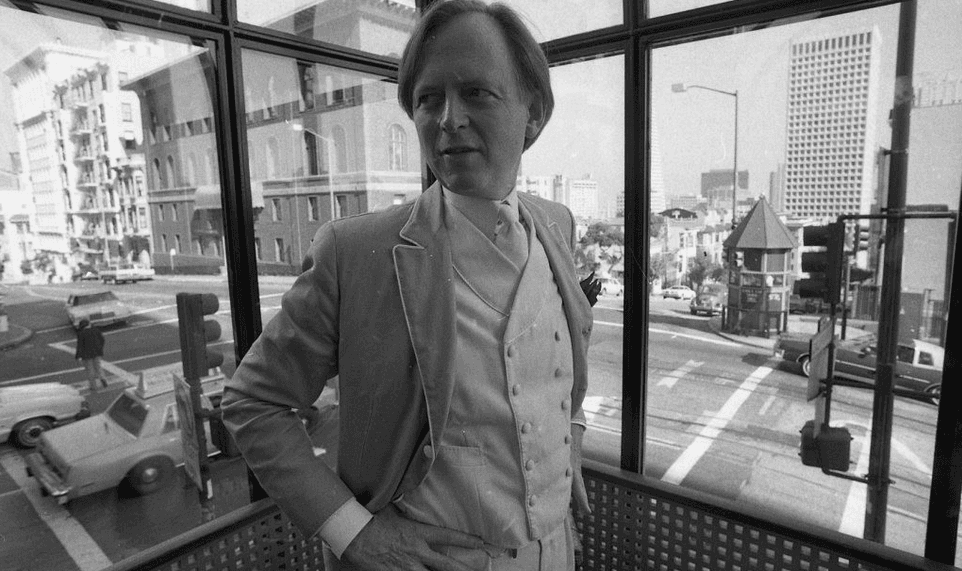

Writer Tom Wolfe in 1981, in "Radical Wolfe." Eric Luse/San Francisco Chronicle/Getty Images/Kino Lorber

Mark Jackson is the senior film critic for The Epoch Times and a Rotten Tomatoes-approved critic. Mark earned a bachelor's degree in philosophy from Williams College, followed by classical theater conservatory training, and has 20 years' experience as a New York professional actor. He narrated The Epoch Times audiobook "How the Specter of Communism Is Ruling Our World," available on iTunes, Audible, and YouTube. Mark is featured in the book "How to Be a Film Critic in Five Easy Lessons" by Christopher K. Brooks. In addition to films, he enjoys Harley-Davidsons, rock-climbing, qigong, martial arts, and human rights activism.

Author’s Selected Articles