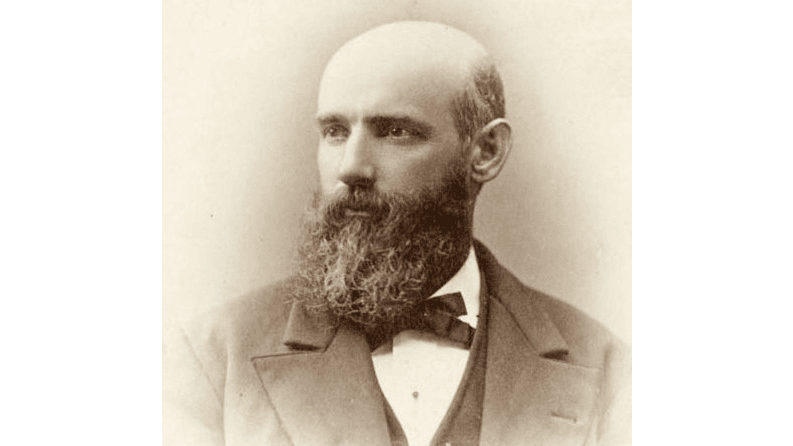

In the high desert of Arizona, just northwest of Tombstone, rests the tombstone of Edward Schieffelin (1847–1897). It is about 25 feet tall in the shape of a prospector’s claim. Its inscription reads: “Ed Shieffelin, died May 12, 1897, aged 49 years, 8 months. A dutiful son, a faithful husband, a kind brother, a true friend.”

What it doesn’t mention is “a determined prospector.” The symbolic shape of the tombstone, however, may make that claim quite clear.