Born in 1844, Bowman Hendry McCalla (1844–1910) was quickly ready for action. When the Civil War began in 1861, the teenage McCalla enlisted into the Army. However, he was not accepted. He therefore pivoted to enter the U.S. Naval Academy. He was admitted in November of 1861 and graduated in November of 1864.

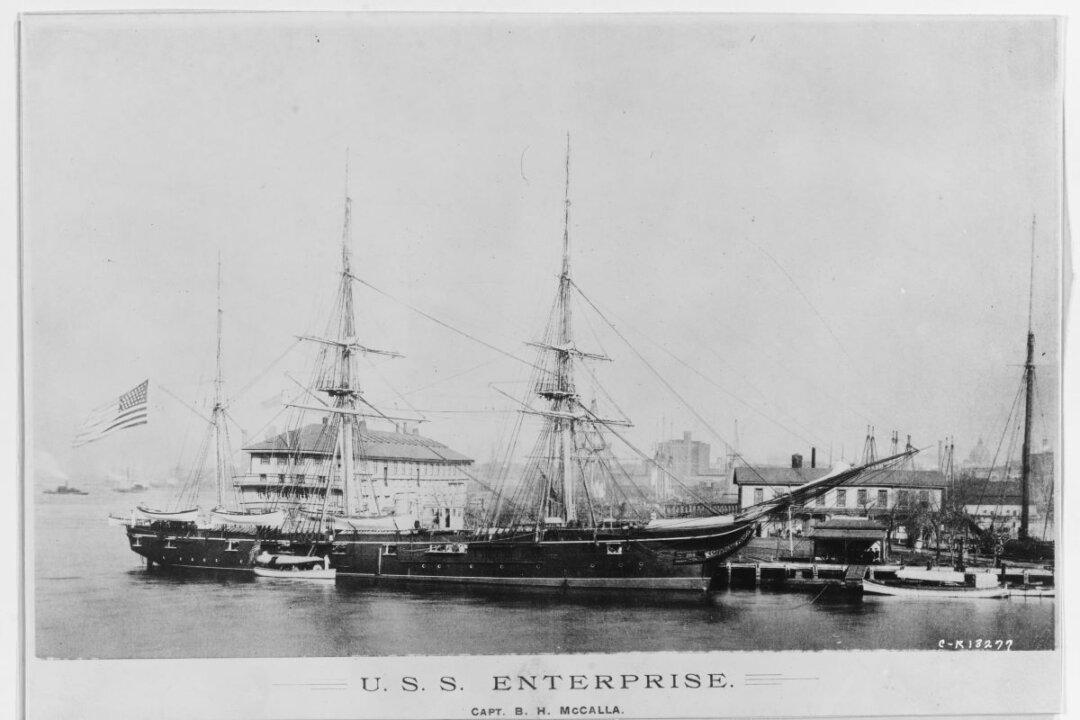

Upon graduation, he was assigned to the Brazil Squadron aboard the USS Susquehanna. McCalla proved a brave and smart seaman, quickly rising through the naval ranks. He was promoted to master in December of 1866, lieutenant in March 1868, and lieutenant commander a brief one year later. On Nov. 3, 1884, he was promoted to commander. It was from this point on that the U.S. Navy—and, therefore, he—witnessed plenty of action.