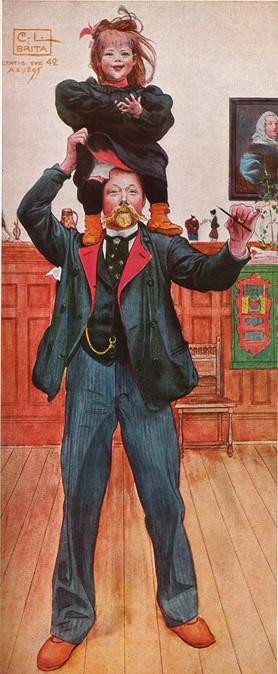

Many artists paint self-portraits over the course of their careers. We see them as they want to be seen, prominent in society, in rich clothing, perhaps holding a symbol of their importance.

In one of his self-portraits, “Brita and Me (self-portrait)” (1895), Swedish artist Carl Larsson (1853–1919) stands, feet spread, on a worn plank floor. He is decked out in a blue suit lined in red and wears an expression of pure joy, for on his shoulders he carries the symbol of his importance—his child.