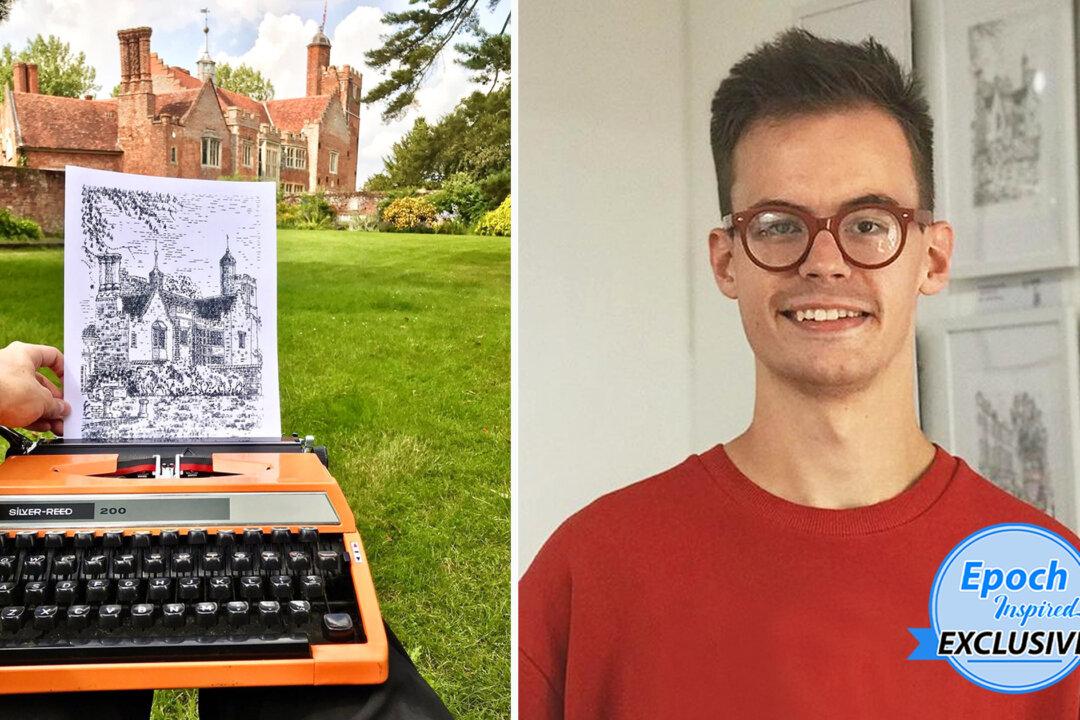

Using only a typewriter as his tool, a young British architecture student is making waves in the art world with his incredible renditions of country and cityscapes.

James Cook, 24, of Braintree in Essex, England, hand-renders each “typicition” in ink using skillful combinations of the keys on a typewriter. For Cook, experimenting with typewriters began while at college studying fine art seven years ago.