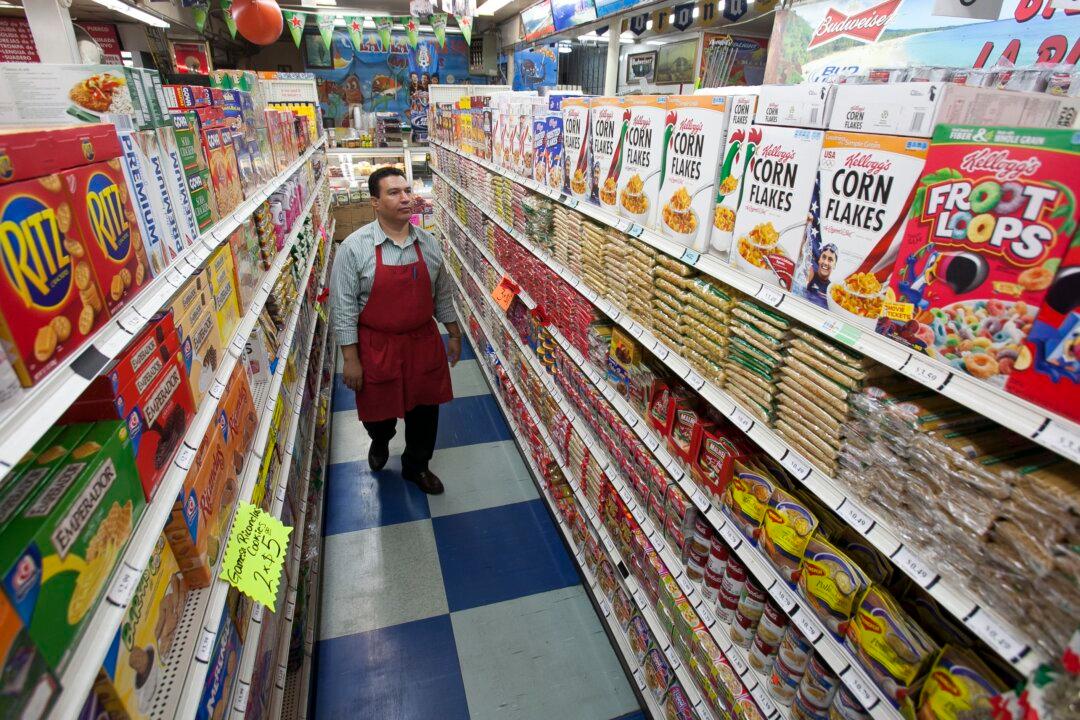

Congress has finally agreed on a national GMO labeling law, but anger and upset is raging across the country from those who feel the law’s framers betrayed the American consumer.

For years, the overwhelming majority of Americans have responded consistently in polls that they want to know if their food contains genetically modified organisms, meaning if it’s grown from seed that has been genetically altered in a lab setting. Over 60 countries already require labels, or restrict GMOs.

Those who oppose the draft legislation say it contains huge loopholes that could allow up to 90 percent of GMOs to escape the labeling requirement.